Content

Content

Hospitals

7.1. Institutional structure

Service delivery responsibilities

- The Commission’s work focuses primarily on the hospital sector, rather than the wider healthcare sector, as hospitals are the most infrastructure-intensive part of the sector. The hospital sector includes both public and private hospitals. The broader healthcare sector includes primary healthcare services (such as general practitioners) and other community healthcare services (such as community health providers and specialist services). While the broader healthcare sector is not formally included in our infrastructure demand analysis, there are significant interactions between the sectors that need to be considered.

- New Zealand has recently adopted a model with a single centralised Crown entity (Health New Zealand/Te Whatu Ora) that provides public hospital services. Public hospital assets are owned, funded, and managed through the single entity structure.

- In addition, private hospitals are operated by various commercial and non-profit entities.

Governance and oversight

- The Ministry of Health monitors the performance of Health New Zealand. It is responsible for health policy and planning. It is also responsible for the regulation of public and private hospitals under the Health and Disability Services (Safety) Act 2001.

- Oversight tends to operate via budget and performance targets to improve health outcomes within funding envelopes.

7.2. Paying for investment

Public funding

- The Government funds around 80% of the cost of health and disability services through taxation (around 70% contribution) and the Accident Compensation Corporation (ACC) levy (around 10%). Other costs are met by users directly and via private insurance. Public hospitals generally provide services free of charge, but with services rationed using waiting lists. Broader healthcare services are subsidised but often have co-payments paid by users.

- The Government sets an annual budget for broad categories of health spending, with Health New Zealand then allocating funding to specific services and regions. ACC funds healthcare for accident recovery through an insurance model, with services provided by public and private providers.

- Some hospital services are funded through private insurance and out-of-pocket payments by users. These are generally used to gain faster access to specialist treatment (such as avoiding public hospital wait times) or to access services not funded by the public system (for example, unfunded cancer treatments). Some healthcare services are also funded by voluntary organisations and private donations, supplementing public funding.

7.3. Historical investment drivers

- Need for hospital infrastructure is driven by population and demographics, income and standards growth, and changes in medical technologies and clinical services delivery methods.

- Investment in hospital infrastructure as a share of GDP peaked in the period between 1960 and 1980. At first, much of this investment was likely in response to population growth, as hospital capacity increased markedly over the period. Over time, expenditure appeared to shift towards improving the quality of existing facilities, which may be a response to medical innovations and higher community expectations.

- Hospital infrastructure is one part of a much wider health system that contribute to health outcomes, ranging from specialist hospital workforces to primary care services to public health promotion. Hospital services are often provided to treat acute and severe health need. A goal of the wider health system is to prevent, manage and treat health needs earlier, often avoiding the need for acute hospital services. Therefore, the effectiveness of the wider health system at preventing and managing health needs is a determinant of the need for infrastructure.

7.4. Community perceptions and expectations

This section summarises what we know about the New Zealand public’s perceptions and expectations of the health and hospital sector, at a national level.

- The health system (healthcare and health infrastructure) is a consistent concern and enduring top priority for New Zealanders, across a range of surveys and over time.195

- While overall, New Zealanders would prefer to spend more efficiently on public services and infrastructure, rather than more, health is perhaps the main exception. Most New Zealanders support spending more to improve health services (either via new funding or reallocating funding).196

- While most surveys do not speak to the relative importance of healthcare services versus infrastructure, ageing hospital infrastructure was identified as a priority concern in one recent survey.197

- In a nationally representative survey undertaken by the Commission as part of consultation on the draft National Infrastructure Plan, 35% of New Zealanders reported that hospital services meet or exceed their needs, while 65% reported it somewhat or consistently fails to meet their needs.

7.5. Current state of network

New Zealand’s difference from benchmark country average

Comparator countries: Australia, Denmark, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. Similarity based on income, population aged 4 and below, and 65 and above, urban population, public coverage of core set of services. Percentage differences from comparator country averages are based on a simple unweighted average of multiple measures for each outcome. Further information on these comparisons is available in a supporting technical report.198

- Our benchmarking analysis focused largely on health infrastructure measures, rather than overall health system measures. Across most metrics we gathered, New Zealand falls towards the lower end of its comparator countries.

- New Zealand’s infrastructure spending per capita is below average relative to comparator countries.

- New Zealand has a relatively low number of hospital beds, although this may reflect how countries deliver healthcare. We also appear to have comparatively low amounts of some medical equipment, like PET scanners or gamma cameras.

- Waiting times for elective surgeries, which could partially reflect infrastructure availability (operating theatres, equipment), are higher than most comparator countries.

- There is some evidence of deteriorating quality of assets. While building envelopes of hospitals are mostly in average to good condition, sitewide infrastructure is in poorer condition, and the average age of hospitals is high compared to the United Kingdom (which was the only comparator country which had comparable hospital age data).

7.6. Forward Guidance for capital investment demand

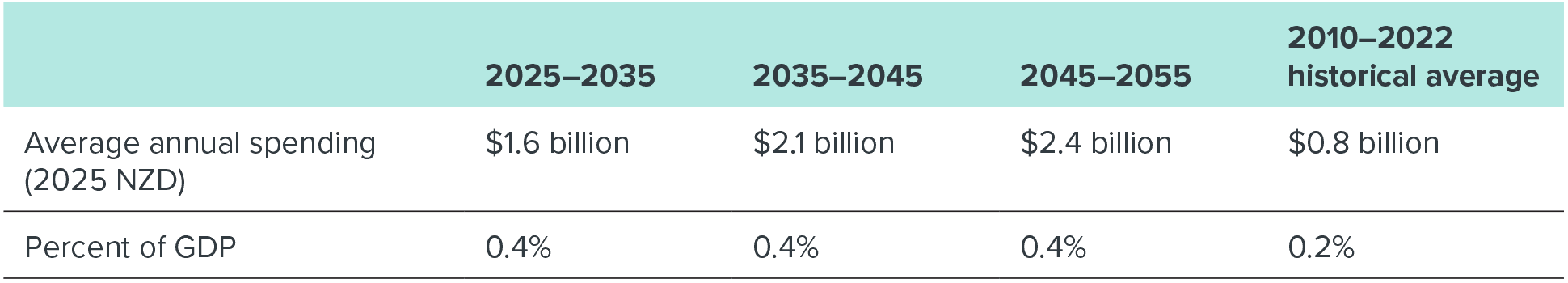

Forecast investment levels for hospitals

This table provides further detail on our Forward Guidance, which is summarised in Chapter 3. Further information on this analysis and the underlying modelling assumptions is provided in a supporting technical report.199 Our investment outlook is primarily focused on hospital infrastructure and fixed assets therein, rather than other infrastructure such as general practitioner offices or community health centres.

- We anticipate a significant uplift in the share of GDP being spent on health infrastructure to meet the growing needs of an ageing population. Changing models of care and major medical innovations may ease demand for hospital services or shift delivery into the community. However, it is likely that population ageing will put upward pressure on hospital demand, and some medical innovations may increase demand for hospital services.

- Renewals of existing stock built during the boom period will also contribute to rising investment requirements over the next 20 years.

- Low levels of investment in the 1990s and since the mid-2010 likely led to deterioration of the hospital estate, creating a backlog of renewals and maintenance.

7.7. Current investment intentions

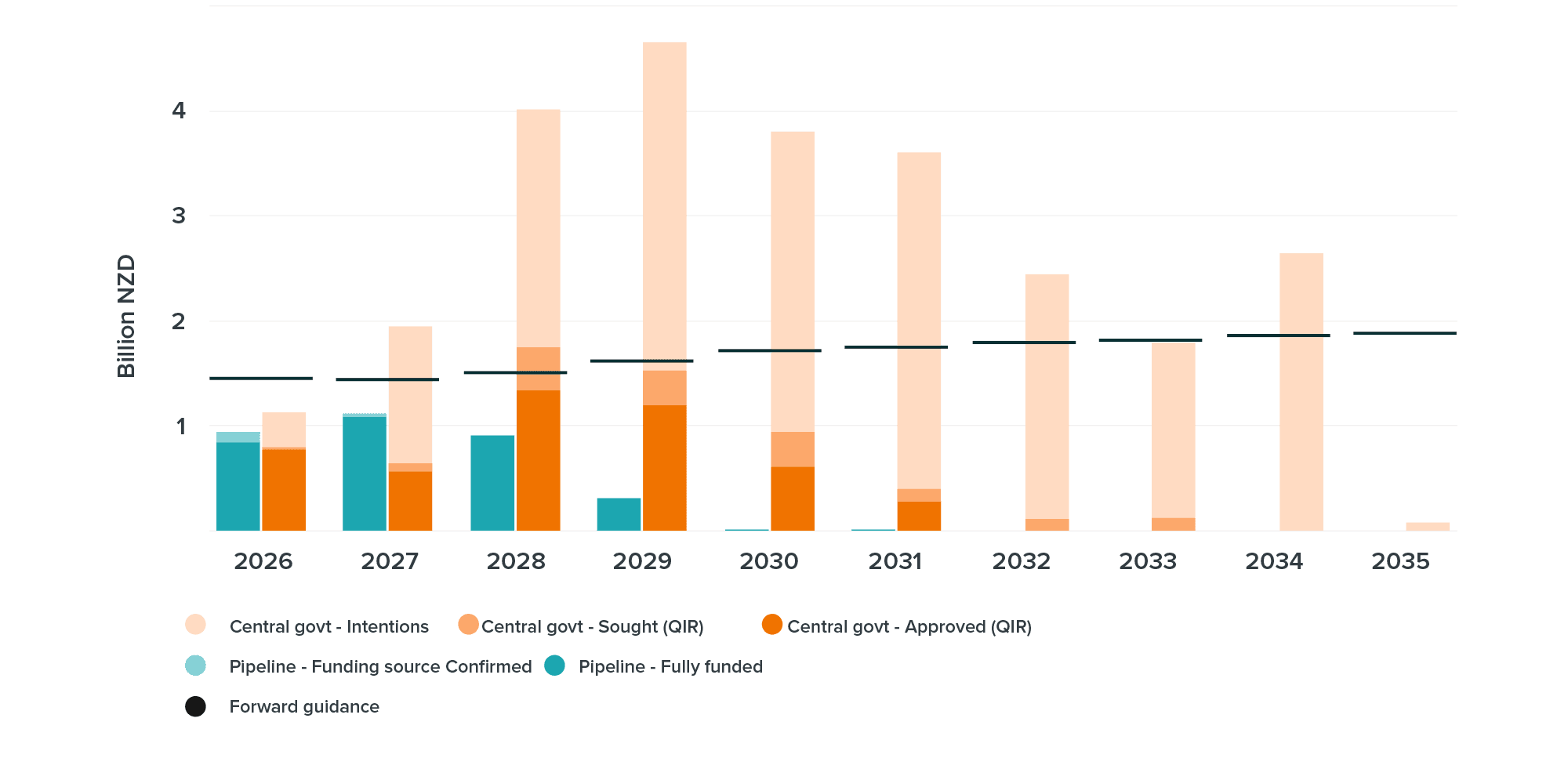

- The following chart shows that projected spending to deliver initiatives in planning and delivery in the Pipeline (turquoise bars) and approved programme-level intentions in central government’s reporting to the Treasury’s Investment Management System (orange bars) are lower than the Commission’s investment demand outlook (black lines) over the 2026–2035 period. However, the full value of investment intentions reported to the Investment Management System are higher than the Commission’s investment demand outlook.

- Information currently in the Pipeline is focused on fully funded initiatives and does not indicate work in planning. Based on investment intentions reported to the Investment Management System we expect significant amounts of planned and unfunded investment to be added to the Pipeline over time. The Health Infrastructure Plan sets out over $20 billion of investment intentions in the health sector.

Figure 52: Hospitals investment intentions

This chart compares two different measures of future investment intentions with the Commission’s Forward Guidance on investment demand. The turquoise bars show project-level investment intentions from the National Infrastructure Pipeline, distinguishing based on funding status. The orange bars show the measure of investment intentions from central government’s reporting of infrastructure-specific initiatives provided to the Treasury’s Investment Management System, again distinguishing by funding status. The black lines show the Commission’s Forward Guidance on investment demand. This reflects all asset classes, whereas the investment intentions are restricted to infrastructure assets.

7.8. Key issues and opportunities

- Asset management and investment planning: As the main funder and provider for health, central government has an opportunity to improve the quality of asset management in the sector. This will be critical as needs in the sector grow. Procurement and financing options that embed asset management (like structured leases or public-private partnerships for asset management services) may be an opportunity to improve asset management practices for new hospitals.

- Coordination: Given the growing needs in the sector, investment plans initiated by Health New Zealand will need to be connected to wider Budget processes managed by the Treasury.

- Project appraisal: As many hospitals prepare for renewal, ensuring their replacements are the optimum size and not overdesigned will help to manage pressure on funding availability. An important enabler of this will be long-term service planning of hospital services. This will inform when it makes sense for a local hospital to provide a service, or whether it is safer, higher quality and more efficient for the service to be provided from a larger hospital covering a wider catchment area. Better planning, appraisal and procurement can also help identify cost efficiencies, maximising what can be delivered within limited health funding.

- Changing models of care: Given the significant growing needs of the sector, wider changes are likely needed to help slow the growth in demand for acute hospital services. This could include consolidating hospital services in fewer hospitals to improve efficiency and quality, changes in models of care to shift services into the community, better integration between primary and secondary care to minimise hospital stay times and treat health needs earlier, and greater investment in prevention and population health services to reduce the need for acute hospital services.

- Efficient regulation and funding: Medical innovation introduces considerable uncertainty in health investment. Historically, these innovations have reduced the need for health infrastructure (such as breakthrough medications) but also increased them (scanning machines). Regulation and funding needs to be adaptable.

- Equity: Access to equitable health services is a top priority for New Zealanders, yet there are inequities in accessing health infrastructure between different locations and for different groups.