Content

Content

Flood protection

14.1. Institutional structure

Service delivery responsibilities

- Flood management in New Zealand is a devolved responsibility, with regional and territorial authorities taking the lead in mitigating natural hazard events under a range of Acts including the Local Government Act 2002, the Soil Conservation and Rivers Control Act 1941, the Resource Management Act 1991 and the Civil Defence Emergency Management Act 2002. This regional approach allows for tailored solutions to local flood risks. However, there is also a push for a more coordinated national approach to ensure consistency and address the increasing challenges posed by climate change.

- Regional councils are the lead agencies responsible for delivery, including the planning, funding, construction, and maintenance of major flood control schemes within their catchments, as well as developing catchment management plans and flood hazard maps.

- Territorial authorities are responsible for managing local stormwater networks and land-use planning, which must integrate with the wider regional flood management framework.

- New Zealand employs a variety of structural measures to mitigate the risk of flooding, primarily relying on a network of stopbanks, flood walls and groynes. While stopbanks are the primary defence, other methods are also employed. River diversions, like the Moutoa Sluice Gates on the Manawatū River, redirect excess water to protect downstream communities. Although New Zealand's large dams were primarily built for power generation and irrigation, they also play a role in buffering major floods. Nature-based solutions are also being increasingly used.

- There are various flood protection schemes distributed across the country and managed by regional councils. The Te Uru Kahika National Flood Risk Resilience business case states there are 367 such protection schemes.

- Private landowners are responsible for managing drainage on their own properties, managing overland flood paths and, in some areas, smaller, private flood protection works.

Governance and oversight

- Flood protection is managed through a devolved, multi-level structure where central government provides the legislative framework. As part of the current changes being made to the RMA, the current Government is considering introducing National Direction on Natural Hazards (ND-NH), which would provide overarching national planning direction for identifying and responding to natural hazard events.

- Governance is exercised at the regional level. Regional councils interpret national laws to create specific regional policies and floodplain management plans. Historically, some form of delegation to regional or local governments has been the norm, as with the Soil Conservation and Rivers Control Act 1941 and the Water and Soil Conservation Act 1967, which authorised catchment boards to undertake river control works. Other relevant legislation includes the Civil Defence Emergency Management Act 2002 which provides the framework for emergency response.

- Central government agencies also have an active role in flood protection. For example, the Ministry for the Environment (MfE) is developing the ND-NH. The National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA) coordinates central government's response to large-scale emergencies, including major flood events.

14.2. Paying for investment

- Historically, flood management has been funded through a combination of central and local government investment under the Soil Conservation and Rivers Control Act 1941, which allowed for central government loans and subsidies through the then Minister of Works. The Ministry of Works oversaw investment by catchment boards.

- The current model emphasises local responsibility, with regional councils funding flood protection works through targeted rates paid by the communities that benefit from them. This beneficiary-pays approach can create affordability challenges, particularly where small communities face high costs to protect against major flood risks.

- In recent years, central government has committed some funding to flood resilience, including $217 million in 2022 from the COVID-19 Response and Recovery Fund, $22.9 million for Resilient Westport following flood events in 2021 and 2022, $100 million in 2023 for flood resilience projects in areas impacted by Cyclone Gabrielle, and $200 million in 2024 ring-fenced in the Regional Investment Fund.

14.3. Historical investment drivers

- Major investment has historically been reactive, often driven by the aftermath of significant and destructive flood events that highlighted vulnerabilities.

- Much of the proactive investment in the mid-20th century was driven by the need to protect productive agricultural land like the Hauraki and Heretaunga Plains. Key legislation, such as the Soil Conservation and Rivers Control Act 1941, was a direct response to widespread flooding and erosion, establishing the institutional structures (catchment boards) that initiated most of New Zealand's major schemes. These catchment boards were funded through local authority rates.

14.4. Community perceptions and expectations

This section summarises what we know about the New Zealand public’s perceptions and expectations of the flood protection sector, at a national level.

- New Zealand’s infrastructure to reduce flooding was rated as poor/very poor by two-thirds (64%) of respondents in a 2024 survey.217

- New Zealand’s flood protection infrastructure was rated as an investment priority for just under half of New Zealanders, according to one survey.218

- In a nationally representative survey undertaken by the Commission as part of consultation on the draft National Infrastructure Plan, 46% of New Zealanders reported that flood protection services meet or exceed their needs, while 54% reported they somewhat or consistently fail to meet their needs.

14.5. Current state of network

- New Zealand relies on an extensive network of flood protection assets, including at least 5,284km of stopbanks, many of which were designed and built several decades ago to varying standards.

- Some flood protection infrastructure may not be adequate to provide the intended level of protection against the increasing frequency and intensity of rainfall events being driven by climate change.

- There are recognised gaps in the national understanding of the condition and performance of many flood defence assets, making it difficult to accurately assess risk and prioritise investment.

14.6. Forward Guidance for capital investment

- The Commission has not produced Forward Guidance for flood protection infrastructure.

14.7. Current investment intentions

- Regional councils are planning significant capital works programmes focused on upgrading key flood defence schemes to provide greater resilience against larger flood events, such as raising stopbanks in Hawke's Bay and the Waikato.

- Investment is being targeted at schemes that protect major urban areas, economically vital agricultural regions, and critical national infrastructure.

- Alongside strengthening physical infrastructure, councils are also investing in non-structural measures and nature-based solutions, including improved flood warning systems, catchment-wide management plans, and stricter land-use controls.

- A recent report by Te Uru Kahika estimated that strengthening flood resilience would cost $5 billion over the next 10 years. The most significant driver for future investment is climate change adaptation.

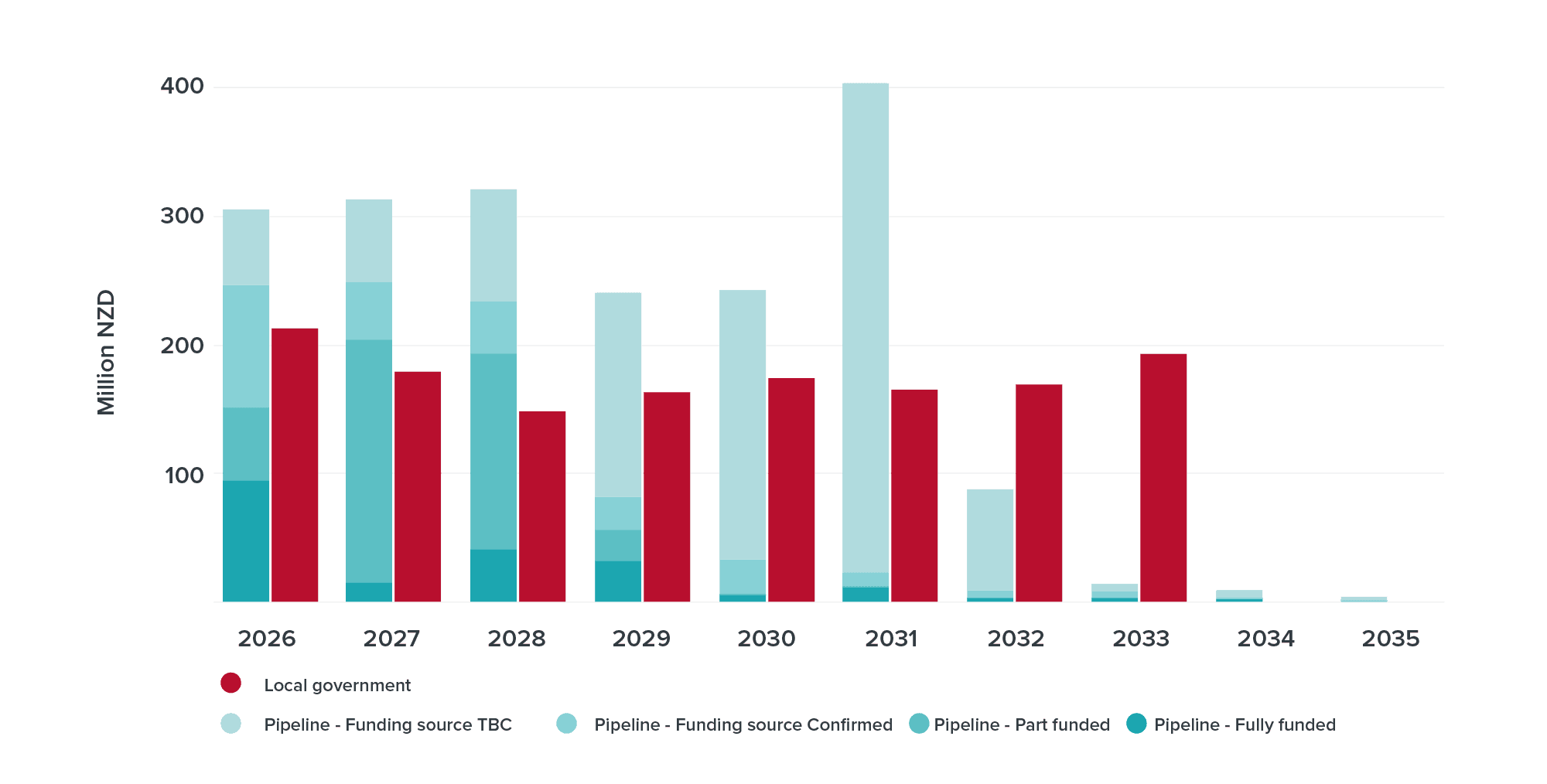

Figure 59: Flood protection investment intentions

This chart compares two different measures of future investment intentions. The turquoise bars show project-level investment intentions from the National Infrastructure Pipeline, distinguishing based on funding status. The red shows the measure of investment intentions based on the Commission’s modelling of portfolio-level data from local government long-term plans. The Commission has not produced Forward Guidance for this sector.

14.8 Key issues and opportunities

- Funding and incentives: Future policy requirements will likely require assessments of the impacts of flood hazards to balance insurance and incentive effects. This includes assessing the costs and benefits of a wide range of different options, including physical protection, avoiding flood-prone areas using land-use planning changes, managed retreat/relocation from inhabited flood-prone areas, and accommodating the effects of flood events by using pumps and stormwater systems. These responses should be proportionate to the size of the flood hazard.

- Asset management and standards: The reactive and fragmented nature of past investment created an inventory of legacy assets with varying standards and unknown performance capabilities, posing a significant challenge for future risk management. The absence of consistent national engineering design standards has further compounded these issues, highlighting the need for greater standardisation to improve resilience and reliability.

- Non-built solutions: There is a significant opportunity to better integrate structural countermeasures, like stopbanks, with non-structural solutions, such as floodplain restoration, nature-based solutions, and managed retreat, to create a more sustainable and resilient long-term approach.

- Coordination: The benefits of flood protection can be diffuse across a whole community, business and infrastructure providers (both government and commercial). Flood protection can also have economies of scale, where it is more efficient to protect a whole area from flooding than each individual beneficiary making investments (for example, elevating individual properties or pieces of infrastructure). Different approaches to funding and financing flood protection infrastructure could help to overcome these coordination challenges.