Content

Content

Defence

11.1. Institutional structure

Service delivery responsibilities

- The New Zealand Defence Force (NZDF) is the singular agency charged with the responsibility of defence in New Zealand. It is part of a trio of organisations providing defence and security for the country, the others being the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service and the Government Communications Security Bureau. Defence has three main functions under the Defence Act, including defence of New Zealand and protection of its interests (for example, patrolling the Exclusive Economic Zone), contributing forces to the United Nations and other collective agreements, and providing humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (both in New Zealand and overseas).

- NZDF includes the three core armed service branches of New Zealand Army, Royal New Zealand Navy (RNZN) and Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF). These entities work separately and jointly to achieve government defence and security outcomes, maintain the effectiveness of their current capabilities and assess the operating environment for future requirements that will drive investment.

Governance and oversight

- The Defence Act 1990 is the governing legislation that established the NZDF and defines the roles and responsibilities of the Minister of Defence, the Chief of Defence Force, and the Secretary of Defence. The Defence Capability Plan (DCP) is a multi-year plan outlining the Government's intentions for investment in defence capabilities, including major infrastructure projects. The 2025 DCP signals a significant increase in spending. Defence Policy and Strategy Statements are high-level documents that set the strategic context for defence activities and capability development.

- Oversight comes through the Minister of Defence, who has statutory authority for the control of the NZDF. The Ministry of Defence is the principal civilian advisory body to the Government on defence policy, capability development, and major procurement. It is a separate entity from the NZDF.

11.2. Paying for investment

- The Government retains the sovereign responsibility for the provision of defence and security for the country, funding these responsibilities through general taxation. They are provisioned through annual Budget appropriations, covering operating expenditure and capital expenditure (maintenance and renewals), as well as individual business cases for the acquisition of new capabilities.

- The Government is beginning to explore alternative financing models to supplement direct taxpayer funding, including the use of PPPs for major redevelopment projects at key bases including Ohakea and Linton. There is increasing interest in working with the local technology sector to co-develop new home-grown military equipment.

11.3. Historical investment drivers

- The establishment of New Zealand’s main defence infrastructure occurred in response to the military needs of the Second World War. This included the main military camps of Papakura (1939), Waiouru (1940) and Linton (1942), while military aviation infrastructure was developed at Ohakea (1939) and Whenuapai (1939).

- Defence investment responds to foreign policy, geopolitical risks, and renewals of existing assets deemed important for New Zealand’s defence capability. Defence capability also plays an important role in responses to natural hazard events. The acquisition of upgraded or new defence capabilities across the three services should trigger complementary investment in physical infrastructure that support these new capabilities (for example, modifications to dockyards, airbases and service facilities).

- Due to the small scale of purchases relative to international partners, New Zealand has often followed our closest allies and those we work with regularly for the acquisition of significant military capital assets. Previously New Zealand has either joined on to the end of production runs for other countries’ assets, or purchased to stay in lockstep with our allies’ capabilities, specifically Australia, for example with ANZAC frigates and the Poseidon P8As aircraft.

- New Zealand's strategic focus on the South Pacific as a key area of operations has driven investment in infrastructure that can support humanitarian aid, disaster relief, and maritime security missions throughout the region.

11.4. Community perceptions and expectations

This section summarises what we know about the New Zealand public’s perceptions and expectations of the defence sector, at a national level.

- New Zealanders’ views about whether to spend more or less on defence infrastructure are mixed and change over time. While in the past about one-in-five New Zealanders agreed with spending more on defence,210 more recent data suggests that about half of New Zealanders may support spending more on defence.211

11.5. Current state of network

- The current value of NZDF assets (excluding land) was about $10 billion in 2024. About $5.5 billion of this is specialist military equipment and almost $4 billion was buildings and infrastructure. Investment (addition of fixed assets) has averaged about $542 million (in 2025 dollars) since 2003, although this has increased in recent years.

- The defence estate currently includes approximately 81,000 hectares of land, encompassing over 4,700 buildings, nine main bases, and two major training areas. This includes specialist defence facilities such as a dry dock, runways, fuel storage, medical facilities, and weapon ranges, horizontal infrastructure (such as 400km of roading), and living, working, and training accommodation for 14,000 personnel.

- Overall, there appears to be evidence that a significant portion of defence assets are aged and potentially no longer ‘fit for purpose’ to support modern military capabilities and personnel. We estimate that investment to depreciation ratios have averaged about 119% since 2003. In eight of those years, total investment (including renewals as well as improvements) was below depreciation, indicating that assets were wearing out faster than they were being improved.

- Key operational hubs such as Devonport Naval Base, Ohakea Air Base, and the Linton and Waiouru Military Camps require extensive regeneration to meet future operational demands, training needs and health and safety standards. Defence housing proposals to the Commission’s Infrastructure Priorities Programme noted that a substantial number of assets are in very poor condition.

11.6. Forward Guidance for capital investment

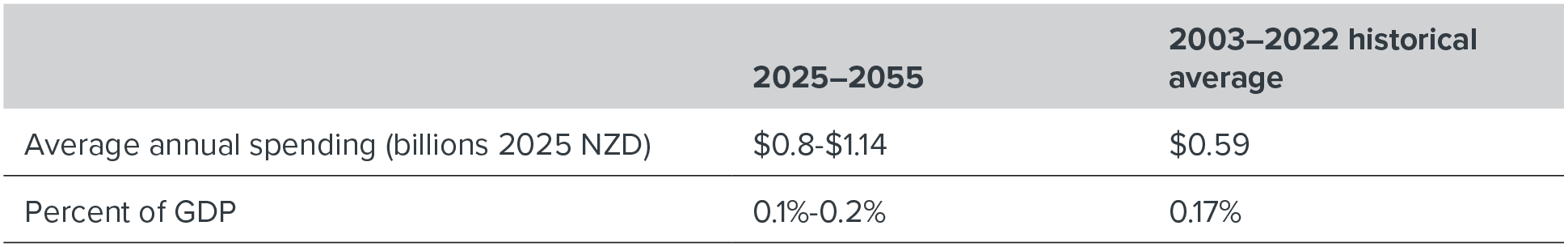

Forward Guidance for Defence infrastructure investment

Note: Ranges are based upon each subsector’s estimated relative share of the total public safety category over the past 10 to 20 years. These shares are derived from the estimated share of capital stock and investment over the period. Data on asset values and investment collected by the Commission from agency annual reports.

- The Commission’s Forward Guidance for defence investment largely projects a state of investment required to maintain and renew existing defence assets over a 30-year period. It does not account for potential catch-up investment for underinvestment in previous years. As such, it should be viewed as a long-run sustainable target.

- The Commission’s Forward Guidance covers investment in the estate, as well as investment in other defence capital assets such as military equipment. This is to assist central government and the Treasury with long-run capital planning.

- Stats NZ classifies defence within the wider public administration and safety asset class that also includes justice, public safety and corrections. The Commission’s Forward Guidance above represents our estimate for defence’s share of that asset class. The Commission has collected data on the value of capital investment for public administration and safety and noted that it has rarely exceeded 1% of GDP over the last 100 years, even during the First World War and the Second World War.

11.7. Current investment intentions

- NZDF’s Defence Capability Plan (DCP) is the principal strategic document outlining the Government's long-term vision and planned expenditure for military capabilities, which directly informs the required supporting infrastructure. The Government-approved plan amounts to $12 billion over 4 years which is a major uplift in investment as a share of GDP. The programme covers physical infrastructure and estate regeneration and military capital assets, including ships, aircraft (fixed and rotary wing) and vehicles.

- The DCP includes the Defence Estate Strategy and its associated regeneration programme provide the overarching framework for the entire defence property portfolio. It prioritises investment to align infrastructure with the capabilities set out in the DCP and to regenerate existing assets that are critical to defence outcomes, but are currently unable to support modern needs, such as housing, barracks and a range of horizontal infrastructure assets. Detailed master plans for individual bases and camps, developed in partnership with military service branches, and with private sector consultant expertise, provide a more granular, site-specific roadmap for future development and investment priorities over the next 30 years.

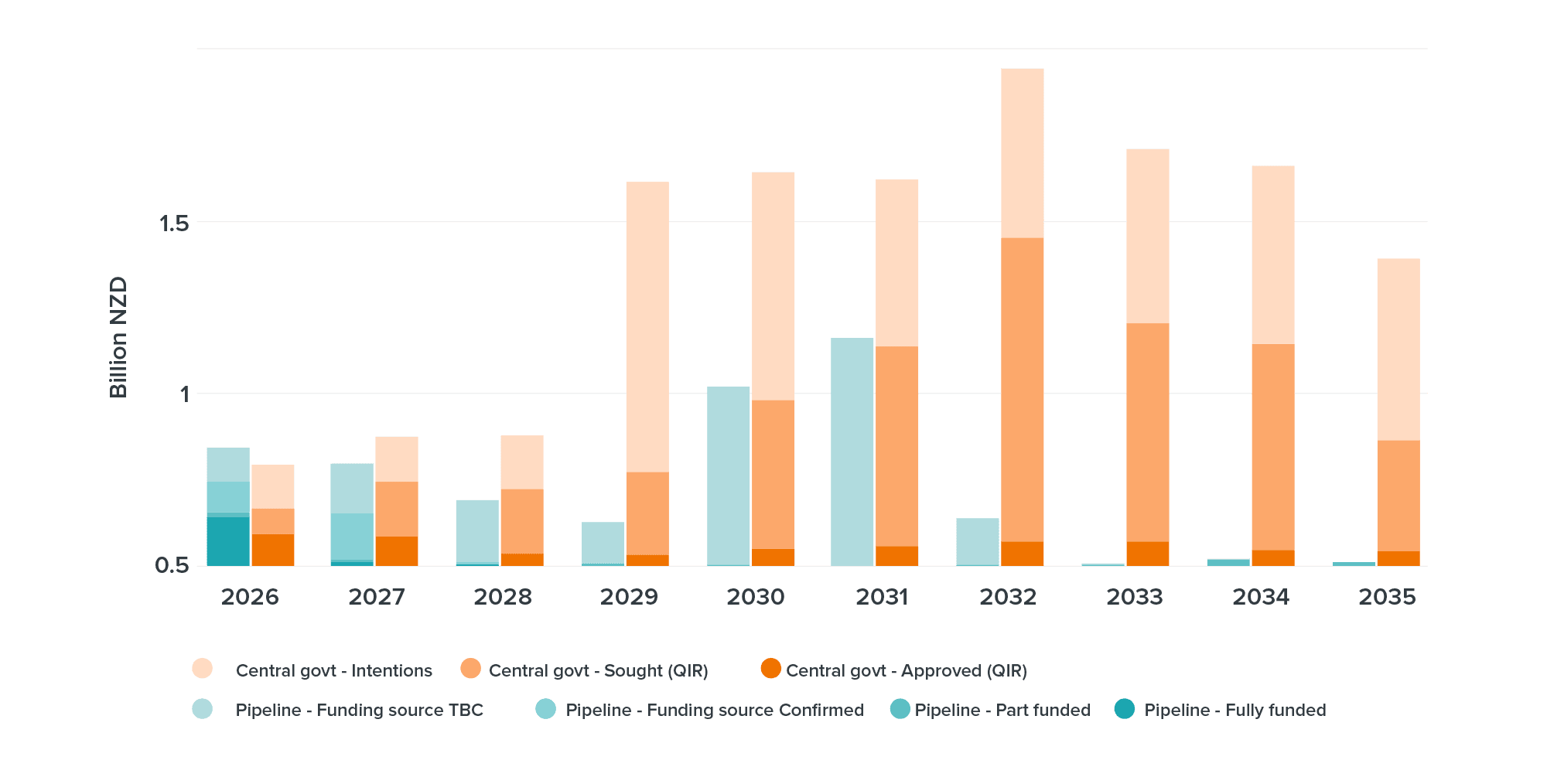

- For defence, our Forward Guidance is largely a long-term indicative target, rather than an annual projection. As such, we have excluded it from the chart below.

- The intentions data is for infrastructure assets only and does not include any special equipment.

Figure 56: Defence investment intentions

This chart compares two different measures of future investment intentions. The turquoise bars show project-level investment intentions from the National Infrastructure Pipeline, distinguishing based on funding status. The orange bars show the measure of investment intentions from central government’s reporting of infrastructure-specific initiatives provided to the Treasury’s Investment Management System, again distinguishing by funding status. It does not show a comparison with the Commission’s Forward Guidance on investment demand as work is ongoing to align data definitions.

11.8. Key issues and opportunities

- Asset management: A primary challenge is the cost of the required infrastructure regeneration after an extended period of low investment in renewals for vital existing infrastructure. Other issues include managing the complexity of major construction projects, addressing skill shortages in the construction sector, and ensuring investments are resilient to climate change impacts.

- Service level enhancements: The defence estate regeneration programme offers a chance to improve energy efficiency and reduce long-term operating costs when fully implemented. There is an opportunity to deepen strategic partnerships with the private sector, fostering innovation in construction and financing. Furthermore, targeted infrastructure upgrades can significantly enhance interoperability and training opportunities with New Zealand's key international allies.

- Growing geopolitical uncertainty: While forecasting need for defence infrastructure is difficult, geopolitical trends suggest a less benign future international environment, greater competition between great powers and more uncertainty about the future of the rules-based international order. Current conflicts are impressing the need to account for technological change when procuring new capabilities and for modernising existing platforms. Greater investment in defence capability will likely be needed, but it is important that investment in new capabilities doesn’t come at the expense of addressing maintenance and renewal needs, which support the effectiveness of frontline capabilities.