Content

Content

6.2. Accelerating electricity investment for growth and decarbonisation

Te whakatere i te haumitanga hiko mō te tipuranga me te whakaheke tukuwaro

Context

Energy infrastructure underpins economic growth and is central to achieving net zero carbon targets. New Zealand’s historically affordable, reliable and low-carbon electricity has been a competitive strength, but the system now faces a decisive transition: expanding the supply and use of low-carbon electricity while managing declining domestic natural gas supplies.

Energy infrastructure faces significant change over the next 30 years. Electricity and gas infrastructure, including electricity generation, transmission and distribution and gas transmission and distribution, must adapt to changing demands. This infrastructure is delivered and operated by commercial entities, coordinated through wholesale energy markets and network pricing mechanisms, and overseen by many agencies and regulators. Government must act predictably in the market-driven energy sector to support consumers, ensuring interventions strengthen rather than distort investment incentives. The focus of the Infrastructure Commission’s advice is on how stronger coordination and predictable, well-targeted interventions can accelerate infrastructure investment.

Energy affordability has come under short-term pressure, and there is an ongoing risk that investment in new generation capacity and storage might lag demand. While fixed-price retail contracts buffer most households and small commercial users, some large energy users may choose to remain exposed to wholesale electricity spot prices. Accelerating investment in renewable generation and storage is essential to restore a more optimal balance between supply and demand and bring average prices down to sustainable levels.120 Electricity generators are investigating a pipeline of future projects with cumulative capacity of more than 40GW – four times the capacity of existing generation.121 Having options allows companies to respond when electricity demand increases.

Electricity usage is projected to increase by more than 60% by 2050 to meet emissions targets.122 Meeting this will require around $26 billion in capital investment above base-level requirements over the next 30 years – or around $835 million per year. Investment will be frontloaded over the next 10–15 years, and the vast majority will need to go towards new generation and associated network upgrades, plus adapting to new technologies and changes in energy use.

Expansion of renewable energy sources can lower prices but it comes with new challenges. New renewable generation can lower average prices and encourage increased electricity use, as it displaces higher-cost thermal generation and reduces reliance on imported fuels. Predictable policy and regulatory settings can reduce financing risk, which in turn lowers the cost of new investment. However, affordable and reliable electricity supply also depends on maintaining enough flexible generation and storage to manage short-term peaks, seasonal peaks, and dry years. As gas declines, this ‘firming’ capacity is likely to come from a mix of generation sources, battery storage, and demand response mechanisms.

The Government recently reviewed the energy market and is progressing some changes in response.123 They are progressing a market-led package of reforms, as well as initiating a procurement process for a Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) facility.124 The Plan, by contrast, focuses on broader initiatives that can drive credible policy settings, strengthen regulatory oversight and support consumers to create a coherent path forward to navigate the energy transition.

Strategic direction

Energy policy guides a shift towards cleaner and more efficient energy use

Investment in new electricity generation, transmission, and distribution is largely demand-driven. Commercial energy companies only commit to projects when they expect them to be profitable. Demand for these projects depends on factors such as population growth, the structure of the economy, and the uptake of new technologies like electric vehicles, heat pumps, and artificial intelligence, which relies on energy-intensive data centres. Achieving the required rate of generation, transmission and distribution network investment requires demand to grow.

Government policy and regulation plays a key role in shaping how households and businesses use energy. It can encourage the adoption of new technologies, such as electric vehicles and rooftop solar, and shift demand toward low-carbon sources by pricing emissions through the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS). Government regulation also influences our market settings and how our electricity system is operated to balance supply and demand.

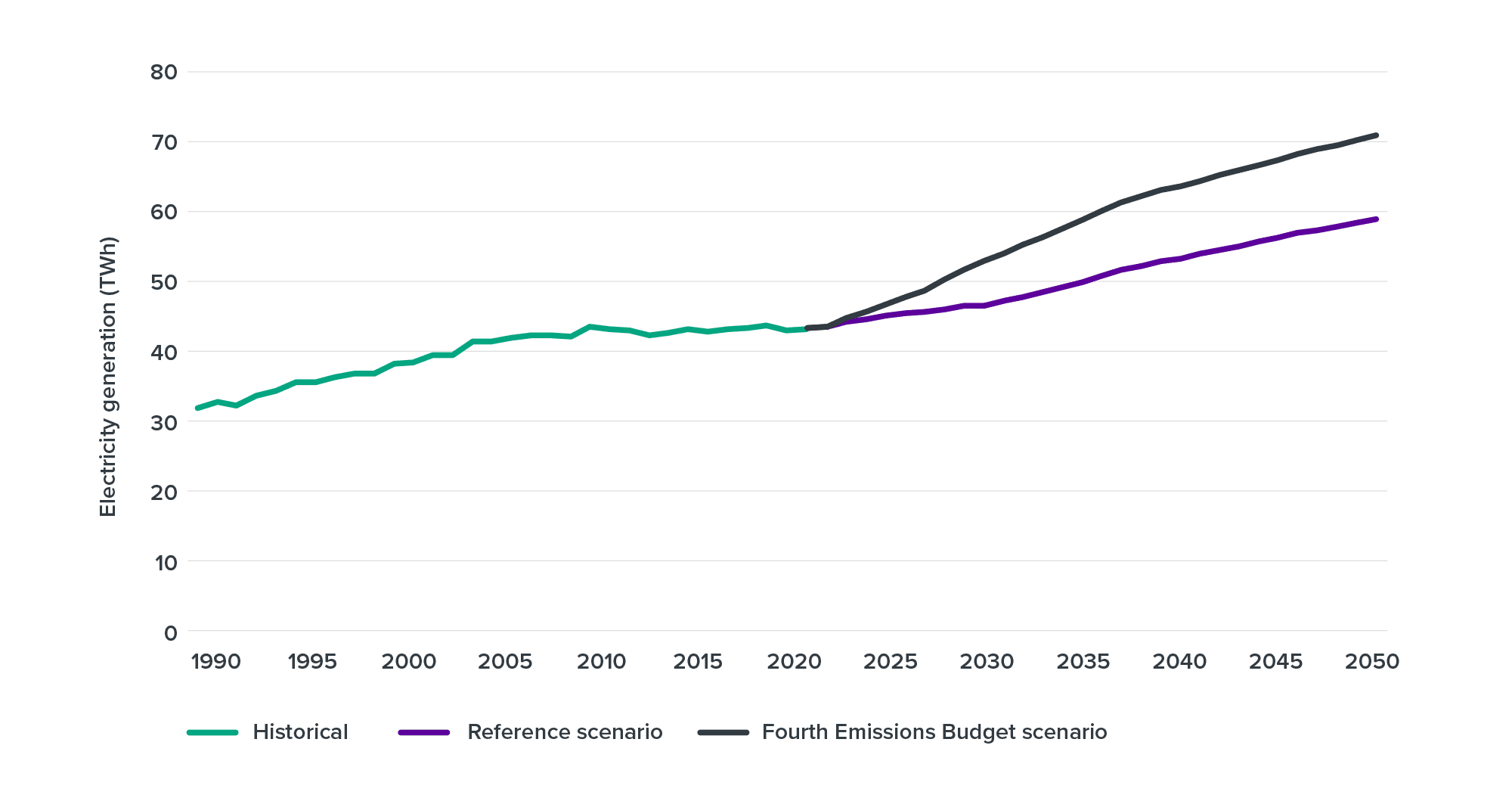

Consistent and credible demand-side policy signals are needed to guide electricity investment. Electricity demand was flat for much of the past 15 years but is beginning to rise as electrification accelerates.125 Yet uncertainty about how fast demand will grow, partly reflecting energy and climate policy settings, makes it difficult for investors to plan. Climate Change Commission modelling (Figure 39) shows that we need to lift electricity use by 60% to reach net zero targets without limiting economic activity. On current trends, we're only on track for half that increase.

There are pathway choices. Different demand growth paths lead to different infrastructure investment outcomes. To unlock investment to grow our energy supply and other economic activity that depends on it will likely involve committing to a pathway and aligning energy and climate policies and tools to achieve it.

We expect to use a mix of approaches rather than a single silver bullet to drive change in energy use and investment. The ETS, where emitters bid for units that represent a single tonne of carbon, remains the primary mechanism for achieving net zero targets. However, this influential policy tool needs recalibration to provide clear signals that will increase renewable generation, fuel-switching, and energy efficiency. Successive Governments’ Emissions Reduction Plans and Energy Efficiency Strategies also recognise a role for complementary demand-side policies to drive targeted gains in areas like transport and industrial energy use. Demand side programmes play a critical role in addressing rising costs of energy. A smarter, more flexible electricity system could deliver savings of around $10 billion (net present value) by 2050.126

Electricity demand needs to rise sharply to meet net zero targets

Figure 39: Climate Change Commission modelling of alternative electricity generation scenarios

Source: ‘Scenarios dataset for the Commission’s 2024 draft advice on Aotearoa New Zealand’s fourth emissions budget’. Climate Change Commission. (2024).

![]()

Priority for the decade ahead

Take a predictable approach to electrify the economy

Forward Guidance: New Zealand needs electricity use to grow by around 60% by 2050 to meet net zero targets without constraining economic activity.127 This requires sustained investment in new generation, storage and networks – supported by stable and predictable policy settings.

What’s the problem?

New Zealand’s energy transition increasingly resembles a limited-overs chase in cricket: the target is clear, but a slow start would make the required run rate rise sharply later. If uncertainty persists now, the transition will become more expensive, more disruptive, and harder to execute.

Investment signals remain mixed. Gas production is declining quickly, yet the future role of gas in firming and security remains unclear. Uncertainty around regulatory responsibilities, climate policy settings, and the timing of key decisions is blurring price signals and delaying investment in alternative generation and storage. And while long-term demand is expected to rise through electrification, industrial change, population growth and uncertainty about the transition path may itself be delaying the demand commitments investors rely on to proceed.

Despite these pressures, there is broad agreement on the destination: more renewable generation, stronger networks, better demand flexibility, and a managed shift away from gas. What is missing is enough clarity and predictability in the near term to keep investment moving at the pace required.

Key actions

- Lock in stable, long-term energy strategies so investors can plan with confidence. This includes clear expectations for the gas transition, security-of-supply reporting, and the role of flexible resources during the shift toward renewables.

- Align climate and energy policies so near-term progress matches long-term goals. Policy, regulatory, and market settings should give consistent investment signals, reducing uncertainty and supporting timely build-out of generation, storage, and networks.

Regulatory and financial settings enable timely investment in electricity supply

Government needs to remove supply-side blockages so that growing demand is met with new supply. Resource management reform, discussed earlier, is a key opportunity to unblock supply – but it is not the only step available.

Transparent, timely information on energy markets supports efficient investment decisions. For example, Transpower’s recent improvements to data on electricity generation pipelines and grid-connection queues have helped identify and overcome barriers to new projects.128 As the energy transition continues and new technologies enter the market, ongoing improvements to information will be needed to guide investment.

Government must use its roles to boost, not slow, the pace of new electricity supply. Poorly targeted or non-commercial interventions, like direct public investment in large-scale generation, can crowd out private capital and weaken long-term incentives to invest. If commercial investors think the Government may step in and undercut them, the result will ultimately be less investment and higher prices. However, strategic Government procurement, like long-term power purchase agreements for energy used by central government agencies, can help boost supply by providing certainty to investors.

Gas users have the information and incentives to navigate the transition

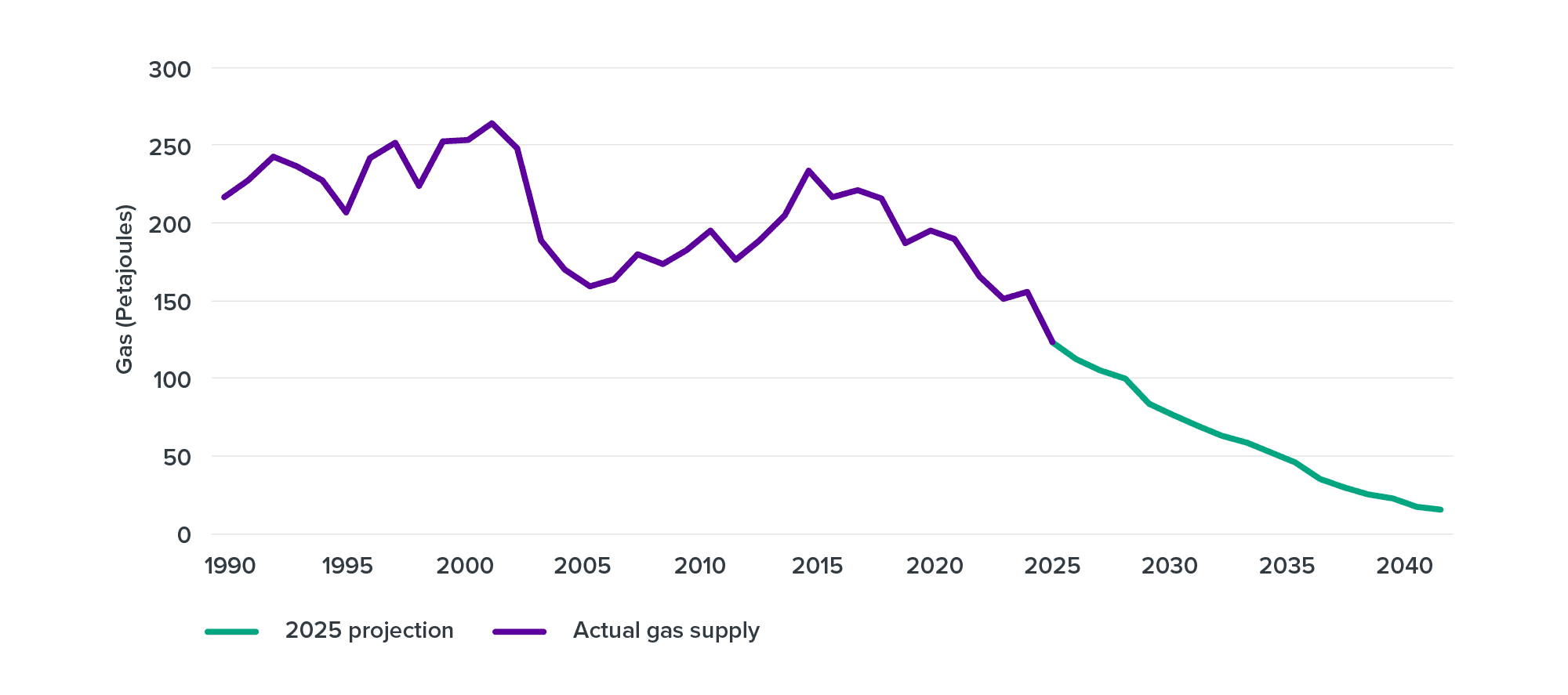

Domestic gas supply is declining rapidly, creating pressure to transition to other energy sources. Production has almost halved over the past decade and is projected to decline at an even faster pace over the next decade (Figure 40). Barring a low-probability discovery of a major new field, gas users – including many industrial firms – will face higher prices and will need to either switch fuels or exit production.129, 130 Sound analysis of the cost of alternative options is needed. For instance, importing LNG may be a commercial option for some individual industrial and other consumers to consider, but it isn’t clear that it would lower average electricity prices.

Declining gas supply has affected electricity prices. Gas has traditionally provided fuel for flexible backup generation during sustained periods of low hydro output and during winter peaks in demand. There are opportunities to use some hydro resources differently, transitioning them from baseload generation to be used more as back-up and ‘firming’ during peak demand and dry years. However, uncertainty about policy settings, regulatory responsibilities and gas availability have confused price signals. This has delayed investment in alternative generation and storage, leading to greater reliance on high-cost coal-fired generation and higher winter electricity prices in the short term.

Managing this transition will require better gas security-of-supply reporting. Current reporting focuses mainly on annual 'best estimate' (proven plus probable, or 2P) gas reserves, leaving energy users and electricity generators exposed to downside risks. More timely and detailed data on reserves, production, and security-of-supply outlooks can help gas users identify and manage these risks.

Industrial and household consumers face the risk of a disorderly transition, if a significant share of gas network customers leave and prices continue to rise. This will have impacts on the owners and users of the gas network, and wider economic and social consequences if more businesses close.131, 132 There are choices about how to manage this transition. For instance, working with businesses and households to accelerate fuel switching from gas to electricity and renewable fuels could support greater energy security while reducing downside risks to existing industries.133

Gas production is projected to decline dramatically

Figure 40: Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment historical gas supply and 2025 gas production projection

Source: ‘Petroleum reserves data’. Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE). (2025).

Consumers have tools and choices to manage their exposure to wholesale electricity prices

Wholesale electricity prices fluctuate. When output from low-cost renewable sources like wind and solar is high, prices are low. When high-cost generation like coal-fired plants or hydro resources reserved for later in the season are needed, prices rise. This variation provides an essential signal for investment in new generation and storage that reduces average and peak prices over time.

For most consumers, what matters is the average electricity price over time, not short-term peaks. Households and small businesses typically buy fixed-price retail contracts that charge the same price regardless of when they use electricity. These users aren't directly exposed to peak wholesale prices, but they benefit from the investment that high peak prices encourage.

While electricity bills have been rising, new investment and demand management techniques can help reduce costs for consumers. Our modelling indicates significant capital investment in electricity infrastructure will be needed, but there are smarter ways to manage demand locally and regionally which could reduce the level of investment and costs to consumers and lead to greater energy reliability and resilience. Energy use initiatives and programmes, including those developed by the Energy Efficiency & Conservation Authority, can help moderate peaks in demand, reducing the risk of ‘scarcity’ prices during the winter and dry years, optimising electricity network build and reducing consumer costs.

Large electricity users can choose how to manage exposure to price swings. They may buy hedge contracts that provide insurance against electricity price volatility, or reduce electricity use during periods of high prices. Peak prices will moderate as more large users offer demand-response services and as more fast-ramping resources like battery storage are built.

More participation in and transparent electricity hedging markets can further align demand and supply. They give retailers, generators, and large consumers access to options for managing price risk while improving revenue certainty for backup generation needed to ensure security of supply. Access to hedging products on reasonable terms for reliable or ‘firm’ generation is particularly important for independent market participants to ensure a competitive market during the transition period to a more renewables-based electricity system. Current examples include the proposal to use long-term contracts to fund refurbishment of the Huntly coal-fired power station as backup for dry years, and a new standardised super peak hedge product that is traded on the over-the-counter market for future electricity supplies, providing more consistent and frequent pricing information to markets.134

Open and accountable oversight keeps public trust in the energy system

Public confidence in the energy system depends on evidence that it is delivering affordable, reliable power and consumers are paying no more than they should. Recent price pressures have raised concerns about market performance, but if investment in new generation does occur, this will restore affordability over time. A contested area is the ownership structure of the ‘gentailers’ – with some arguing for the Government to divest its retail interests, and others advocating for public ownership, or changes in market structure to separate out retail and generation. Ongoing pricing transparency and strong competition will be essential regardless of ownership model.

There is scope to improve regulatory coherence over the gas and electricity sectors. This would ensure regulatory and market performance and associated settings remains credible and responsive to market trends and technological change.135 A particular example is the need to provide clear statutory responsibility for security of electricity supply to a regulator or the System Operator.

As technologies and demand patterns evolve, regulatory oversight must keep pace. Our energy system needs to adapt to new technologies and the more challenging balance between centralised and distributed generation. Done well, this can shift the balance toward consumers. Market rules that worked in the past may not remain effective under new conditions. Periodic, independent reviews of market performance and regulatory settings will ensure that oversight remains credible, responsive, and fit for purpose as the energy transition continues.

![]()

Recommendation 14

Accelerated electricity investment

Establish clear, consistent, and coordinated Government strategies and policies to accelerate electricity infrastructure investment that supports economic growth and emissions reduction.

Implementation pathway

This could be implemented by:

- Setting predictable and aligned energy and climate policies that promote uptake of more affordable renewable energy, including a 30-year energy transition pathway.

- Strengthening coordination, monitoring, reporting and regulation of electricity and gas sectors to keep markets competitive, enable new generation, improve market transparency, and improve energy affordability.

- Leveraging Government energy purchasing power to de-risk investment and support technologies that improve demand management and lower costs.

- Ensuring markets and consumers have adequate information and incentives to manage gas-sector transition risks.

- Supporting the gas transition with better and more timely gas security-of-supply reporting, as well as giving urgent attention to working with the market to address transition risks.

Responsible agencies

Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (lead), working with industry bodies, and energy and competition regulators

Timeframe

3–5 years.