Stability, consistency, and clarity in infrastructure policy are not optional - they're essential.The Connectivity Group Limited submission

Content

Content

6.1. Making resource management work for infrastructure

Te whakamāmā i te whakahaere rawa mō ngā tūāhanga

Context

Resource management legislation is a crucial framework for infrastructure, as it governs how providers interact with the natural and built environments. Councils apply the Resource Management Act (RMA) when developing their regional and district plans, which contain rules about land use and environmental protection. These plans determine what kinds of development can occur, where they can occur, and the conditions required to manage their environmental effects.

There is widespread concern that the RMA isn’t adequately supporting community development aspirations or protecting the environment. The Act, which consolidated dozens of laws into a single, effects-based system, was considered a landmark achievement when it was introduced in 1991. As well as facilitating development and protecting the environment, it was intended to provide better recognition and protection of Māori interests in resource management. In practice, the Act has led to high costs and long delays for consenting much-needed housing and infrastructure projects, as well as environmental failures and inconsistent engagement. The Planning and Natural Environment Bills, which aim to create a more permissive, standardised consenting regime, were introduced as this Plan was being finalised.

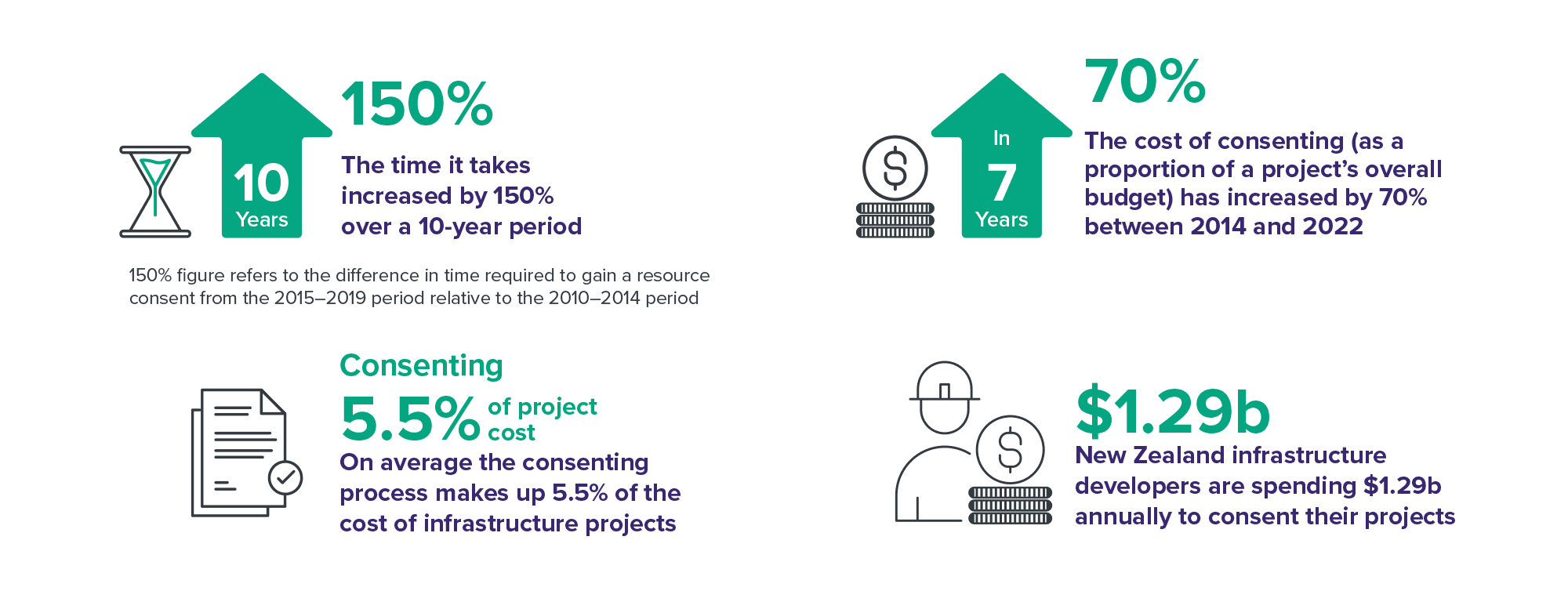

Infrastructure providers spend around $1.3 billion each year on consenting. International comparisons indicate New Zealand may be near the upper end for regulatory approval costs. A typical infrastructure project requires a firm to spend, on average, 5.5% of their total budget seeking a resource consent. For smaller projects worth less than $200,000, the figure is more like 16%. Not only has consenting become more complex and expensive, but processing times have also increased (Figure 37).112

Land use and infrastructure planning are not well coordinated to meet future demand and make best use of infrastructure. Some councils have developed spatial plans to try and manage future growth in a sequenced, affordable way. But out-of-sequence plan changes and the limited legal weight given to spatial planning in the current RMA system is undermining the effectiveness of this approach. In addition, restrictive zoning limits the number of people who benefit from and pay for existing and planned transport and water infrastructure. This lack of coordination between land use and infrastructure provision has exacerbated housing affordability challenges and increased the overall cost of delivering infrastructure.113

A challenging regulatory landscape

Figure 37: The cost to consent infrastructure projects in New Zealand

Source: ‘The cost of consenting infrastructure projects in New Zealand’. Sapere. Commissioned by the New Zealand Infrastructure Commission (2022).

Strategic direction

The regulatory environment better serves New Zealanders

New Zealand needs an efficient legislative and regulatory system. Well-designed and consistently implemented regulation makes it easier for infrastructure providers to invest in and operate infrastructure. It also helps build social licence for infrastructure investment by making sure the impacts on communities and the environment are well managed.

Regulation should improve outcomes in a cost-effective way. Temporary traffic management, for example, is needed to protect workers and road users while work happens in the road corridor. Increased requirements over the last decade had safety benefits but also imposed higher costs on infrastructure providers. Electricity Networks Aotearoa estimates that the daily cost of temporary traffic management for electricity line work tripled between 2019 and 2024.114 The system has now shifted to a less prescriptive, more risk-based approach, though it is too early to assess its impact.

Central government should ‘smooth the path’ for infrastructure by providing enduring, predictable and enabling laws and regulations. Large projects and programmes take years to plan and design. When regulatory or design requirements shift, they must be rescoped, adding costs and delays and undermining the use of standardised, cost-saving designs.

The resource management system is stable, consistent, and easy to work with

The RMA should be replaced with a more effective and efficient system. Key changes should include a focus on regional spatial planning, a smaller number of regulatory plans, setting environmental limits, and enabling infrastructure through national direction. The new system should incorporate existing national directions covering infrastructure, renewable energy and electricity networks.

The resource management system should enable and protect infrastructure. The new system should provide a pathway for managing the impacts of infrastructure that cannot avoid areas where there are environmental limits or significant natural environmental values. It should also set standards for cost-effectively managing the effects of common infrastructure-related activities, such as land disturbance and noise. In addition, infrastructure needs to be protected from the effects of nearby land uses which can limit how assets are operated and maintained.

The system should also protect the environment. New Zealanders value te taiao, the natural environment. Protecting the environment is particularly important for Māori, who have a deep connection with the land, or whenua, and want new infrastructure to improve and integrate into the existing landscape, not damage it. To maintain social licence for development, the new resource management system needs a consistent approach to protecting environmental limits. This may require reviewing the Fast-track Approvals Act to ensure alignment with broader reforms. While the Act has streamlined approvals under multiple pieces of legislation, it has also sparked debate about the balance between economic growth and environmental protection.

The resource management system is supported by sound data and capability

Stronger institutions and clearer capability are essential for the new resource management system to succeed. A clearly accountable entity needs to set, monitor and enforce national standards, while central government must support councils to develop new spatial and regulatory plans. This includes building up its own capacity for spatial planning and developing standard content for land use and natural environment plans.

Good information is needed for good planning, decisions and performance monitoring. Spatial and regulatory plans require integrated geospatial data on environmental values that should be protected, natural hazard risks, existing infrastructure and settlement patterns, and future population and economic scenarios. Central and local government investment is needed to ensure we have robust and consistent data to inform national, cross-regional and local decisions. This should consider the ability of communities with strong regional interests to build up the data and experience needed to participate in resource management processes.

New digital tools can unlock much of the system’s potential. A single national geospatial platform integrating plans and real-time consenting information would give infrastructure providers clear signals about environmental limits, hazards and service needs, while supporting efficient monitoring, reducing permitting risk and enabling better research. This would help the reformed system deliver stronger environmental protection and greater economic benefit.

...streamlining processes must not come at the expense of proper environmental assessment or meaningful engagement with communities.Christchurch City Council submission

![]()

Priority for the decade ahead

Commit to a durable resource management framework

Forward Guidance: New Zealand is partway through a major transition to a new resource management system. Implementing new legislation, national directions, spatial plans and institutions will take several years. Reworking the foundations of the system multiple times adds significant cost, delays major projects, and weakens investment confidence. A stable approach is needed.

What’s the problem?

There is broad agreement that the current Resource Management Act has not delivered the balance between development and environmental protection it was intended to achieve. Successive Governments have sought to reform the system, and despite coming from different perspectives, the most recent efforts share important features: a stronger role for regional spatial planning, fewer regulatory plans, and clearer environmental limits. These areas of alignment offer a solid base for durable reform.

The transition to a new system will take several years and requires new plans, national direction and supporting institutions to be established. When the overarching framework is repeatedly reset, infrastructure providers and councils must constantly adjust project designs and planning assumptions. This slows delivery, increases costs, and makes it difficult to adopt consistent, cost-effective design standards. Frequent system changes also reduce certainty for investors and communities.

A long-term framework that is stable across electoral cycles – open to refinement but not fundamental reconstruction – will provide the clarity needed to plan and deliver major infrastructure over time. Disagreements about aspects of the system such as the role of Te Tiriti o Waitangi/The Treaty of Waitangi and the importance of individual property rights can be addressed through amendments, not complete overhauls.

Key actions

- Commit to improving the new system rather than restarting it. There is likely to be consensus about reforms to better enable and protect infrastructure. Building on areas of cross-party alignment will reduce rework and support long-term reform.

- Provide clear expectations for how national direction and plans will evolve. Stability in rules and pathways will help councils and providers plan investments with confidence.

- Support implementation through strong institutions and consistent guidance. Capability, data systems and national direction will help ensure the new system works as intended across regions.

Spatial planning coordinates land-use planning and infrastructure investment

Spatial planning should help align future growth and infrastructure investment. The process involves local and central government, the private sector and mana whenua sharing information and agreeing how a place might change and grow, as well as areas where development should be avoided due to environmental factors or natural hazard events. Spatial planning also provides a vehicle for central and local government organisations to agree on joint priorities for investment. This is particularly important for major transport investments which are ‘place-shaping’. Coordination between infrastructure and land-use planning can also help ensure infrastructure is used by as many people as possible.

Current spatial planning practices should be strengthened. Some local authorities are already doing spatial planning, but the level of information, mapping conventions and central government involvement varies. Current plans have little legal weight in the resource management system or funding influence. While there are elements of good practice to draw on, there is significant scope for improvement.

To be effective, spatial planning needs legislative heft and influence on investment decisions. The resource management system reforms aim to give spatial planning legal weight. Aligning laws, institutions, incentives and funding is essential to make spatial planning a useful tool to guide how our cities and towns grow. Current reforms must establish a link between spatial plans and infrastructure investment tools such as the Government Policy Statement on Land Transport, regional land transport plans and council long-term plans. In doing so they can help to coordinate central and local government investment intentions and land-use planning.

Spatial plans should help plan for uncertainty and provide high-level direction. Future trends like population growth or technological change are always uncertain. In the face of this uncertainty, spatial plans should consider multiple possible futures and identify public priorities that help guide individual infrastructure investment and development decisions. Spatial plans are a coordination tool – they don’t have to prescribe the exact locations and timing of future infrastructure projects.

Spatial plans should draw on high-quality data. This data on the natural and built environment should be common across other resource management system processes, including regulatory planning. Existing geospatial data should be augmented and standardised where possible, allowing for interoperability between regions. Spatial plans should also be informed by the development of scenarios that capture key drivers of change for a place (such as demographic change and natural hazard risk). Future land use and infrastructure options that respond to these scenarios should be evaluated in terms of their likely costs and benefits.

Spatial planning should inform and be informed by infrastructure investment planning, including the National Infrastructure Plan. The Forward Guidance underpinning this Plan forecasts what a sustainable level and mix of infrastructure investment will look like over the next 30 years, at both a national and regional level. This is based on several drivers of demand, including population growth and the need to renew existing assets that are wearing out. The National Infrastructure Pipeline captures the projects planned by infrastructure providers across New Zealand. Spatial planning should draw on all this information and help to augment it.

Spatial planning can be reinforced by infrastructure providers working together and pricing signals. Coordination between sectors can ensure services are built and operated in a cost-effective way. Road corridors, for example, often accommodate water, energy, and telecommunications networks. Road-controlling authorities therefore try to take a ‘dig once’ approach, coordinating works across multiple providers to minimise disruption and reduce costs.115

Land-use rules allow more people to benefit from new and existing infrastructure

Zoning and other land-use regulations should enable infrastructure to be well used. By clearly setting out what can be built where and at what intensity, land-use regulations directly shape how effectively infrastructure is utilised. While spatial planning identifies where future growth and major infrastructure could go, land-use rules determine the mix of activities in each area, from permitting apartments in one neighbourhood to limiting another to single-storey homes. These rules also influence business operations and other factors that drive how efficiently existing infrastructure is used.

Councils should plan for and enable development opportunities to ensure that growth pays for growth. This requires spatial planning and zoning that facilitates affordable development. The opposite dynamic has been termed the ‘Growth Ponzi Scheme’, where councils grow in ways that make them less, not more financially resilient.116 This can happen when the cost of large new infrastructure networks is met by too few users, leaving councils with insufficient development charges and rates revenue to pay for, maintain and ultimately renew all the required roads, sewerage and water pipes.

Rather than expanding networks at great cost, we need to take a smarter approach to enabling housing and business development. Development needs to be enabled where there is existing spare capacity in water and other critical infrastructure networks. New growth infrastructure needs to be accompanied by plentiful private investment, built in line with demand, and paid for using charges that reflect the true cost of new developments.117

![]()

Priority for the decade ahead

Commit to upzoning around key transport corridors

Forward Guidance: Meeting the needs of a growing population will be the second largest driver of infrastructure investment over the next 30 years, after renewing existing assets. Enabling more housing in places with existing or planned infrastructure capacity means more people get to benefit from and pay for the services that infrastructure provides.

What’s the problem?

Housing affordability remains a major challenge for New Zealand, particularly in fast-growing urban areas. High house prices reflect a shortage of homes in the places people most want to live. Without sustained increases in well-located housing, prices will continue to rise as the urban population grows.

To meet demand and accrue the economic growth benefits provided by denser cities we need planning rules that don't impose a tight lid on development. We also need our fiscally constrained local government authorities and central government to provide supporting infrastructure without further stressing their balance sheets. Some councils such as Tauranga lose money on growth, spending more to service it than they recover through rates and development charges.118

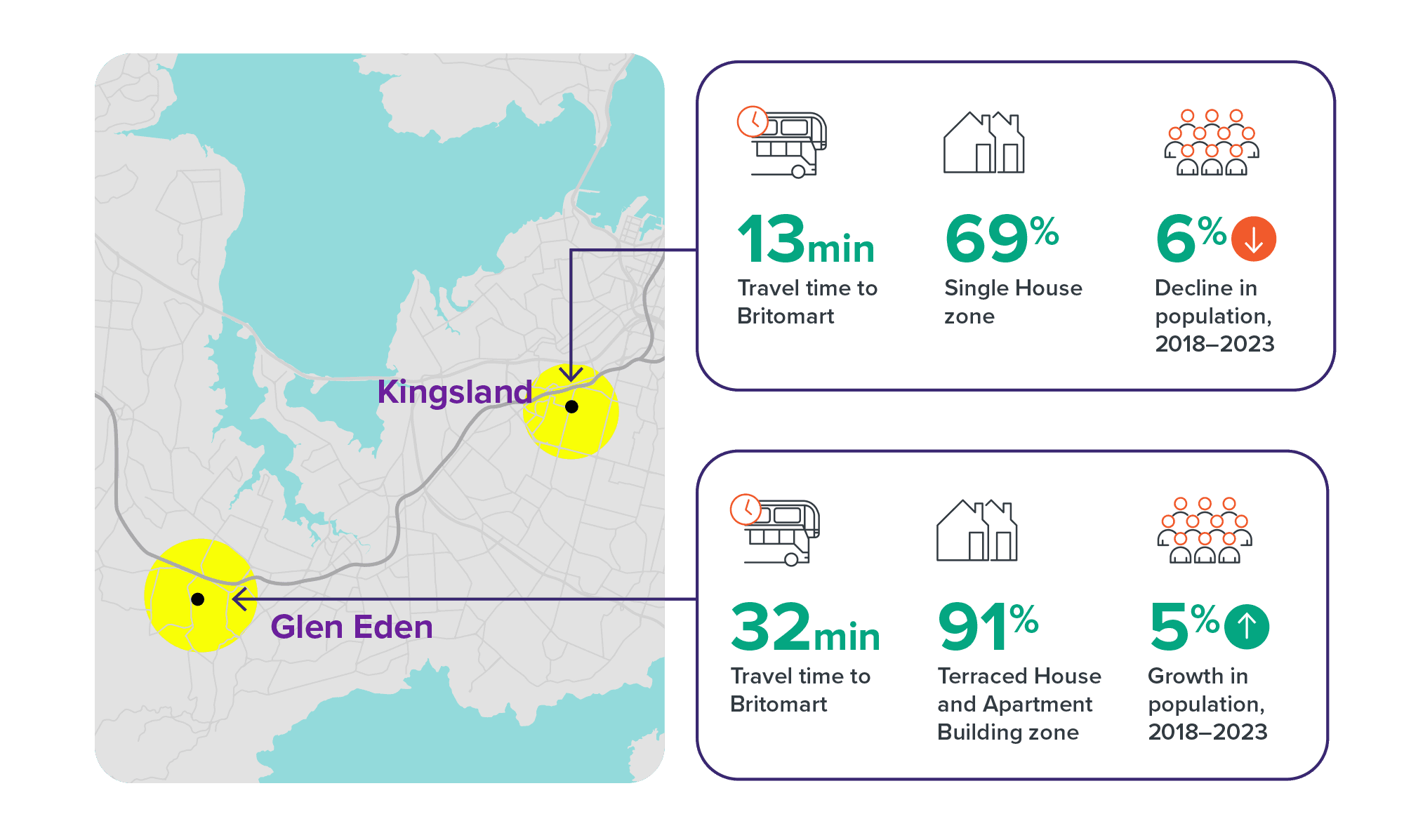

Managing growth costs means enabling development in places that already have capacity in existing or planned networks. A good example is the $5.5 billion City Rail Link in Auckland, which will significantly improve transport access to the inner city. Zoning rules have substantively constrained building new homes and therefore the number of people living near inner-suburban stations such as Kingsland and Mount Eden (Figure 38). Auckland Council is currently progressing a plan change that will allow more homes in these areas, significantly increasing the benefits Auckland gets from this intergenerational investment.

Other cities should follow suit. In Australia, research from Infrastructure Victoria found more consolidated, compact cities had stronger economies and more affordable infrastructure. Their modelling suggested that the infrastructure required to service each home in a more dispersed city cost AD$59,000 (around NZD$68,000) more than in a compact one.119

Figure 38: Aligning development with infrastructure capacity for the City Rail Link

Source: PwC. (2020). Cost-benefit analysis for a National Policy Statement on Urban Development. Report for the Ministry for the Environment. Plus supplementary analysis by the New Zealand Infrastructure Commission. See: New Zealand Infrastructure Commission. (2025). ‘Advice on challenges and opportunities in the transport system: Proactive release’.

Key actions

- Upzone to maximise the benefits from infrastructure. Councils should update their plans to allow more people to live and work near major transport projects such as the City Rail Link. More permissive zoning should also be implemented in areas with spare capacity in the water and transport networks, or where capacity can be added cost-effectively.

- Provide consistent support for enabling policies. Key frameworks – such as the National Policy Statement on Urban Development and the Auckland Council’s proposed Plan Change 120 – can provide the certainty councils and developers need to plan and invest for long-term urban growth.

![]()

Recommendation 11

Stable resource management framework

Commit to maintaining a stable legislative framework for resource management that enables infrastructure while managing environmental impacts.

Implementation pathway

This could be implemented by:

- Maintaining an enduring legislative framework that enables infrastructure while protecting environmental outcomes.

- Investing in capability and digital systems for spatial and environmental data.

- Reviewing how the Fast-track Approvals Act interacts with the new resource management system.

Responsible agencies

Ministry for the Environment (lead)

Timeframe

3–5 years.

![]()

Recommendation 12

Integrated spatial planning

Ensure spatial planning within the resource management system aligns infrastructure investment with land-use planning and regulation.

Implementation pathway

This could be implemented by:

- Developing legislation that gives spatial planning weight in resource management decisions.

- Developing national direction to integrate infrastructure investment planning, including relevant information provided by the New Zealand Infrastructure Commission, into spatial plans.

- Providing national direction on incorporating infrastructure needs, priorities, and funding constraints into spatial planning.

Responsible agencies

Ministry for the Environment (lead)

Timeframe

3–5 years.

![]()

Recommendation 13

Optimised infrastructure use

Set land-use policies to enable maximum efficient use of existing and new infrastructure.

Implementation pathway

This could be implemented by:

- Advancing resource management reforms to direct spatial planning to consider where development is most cost-effective to serve with infrastructure, and introduce national land-use zones for higher-density mixed-use development near rapid-transit corridors and in other locations where infrastructure can support growth.

- Supporting council plan changes that enable efficient use of infrastructure.

Responsible agencies

Ministry for the Environment (lead)

Timeframe

3–5 years.