We need to stop planning infrastructure that cannot be funded. Developing business cases for options that cannot realistically be funded is not an effective use of resources.Engineering New Zealand submission

Content

Content

5.1. Ensuring comprehensive checks and balances for investment

Te whakarite tukanga whānui hei ārai mahi hē i ngā haumitanga

Context

The central government assurance system for infrastructure investment and performance is fragmented and inconsistent. Without a comprehensive system of checks and balances across the investment lifecycle – from long-term asset management and investment plans to the planning and delivery of individual projects – we risk spending our limited infrastructure budget on low-quality investments. As a result, essential renewals and maintenance may miss out.

Decision-makers aren’t getting all the information they need to assess how agencies are managing their infrastructure. Good assurance systems ensure decision-makers have access to independent, robust assessments to guide investment choices. The existing Investment Management System isn’t fully meeting this aim. For example, there is no formal, standardised process for assessing long-term asset management and investment plans, or how agencies are looking after their existing assets in practice.

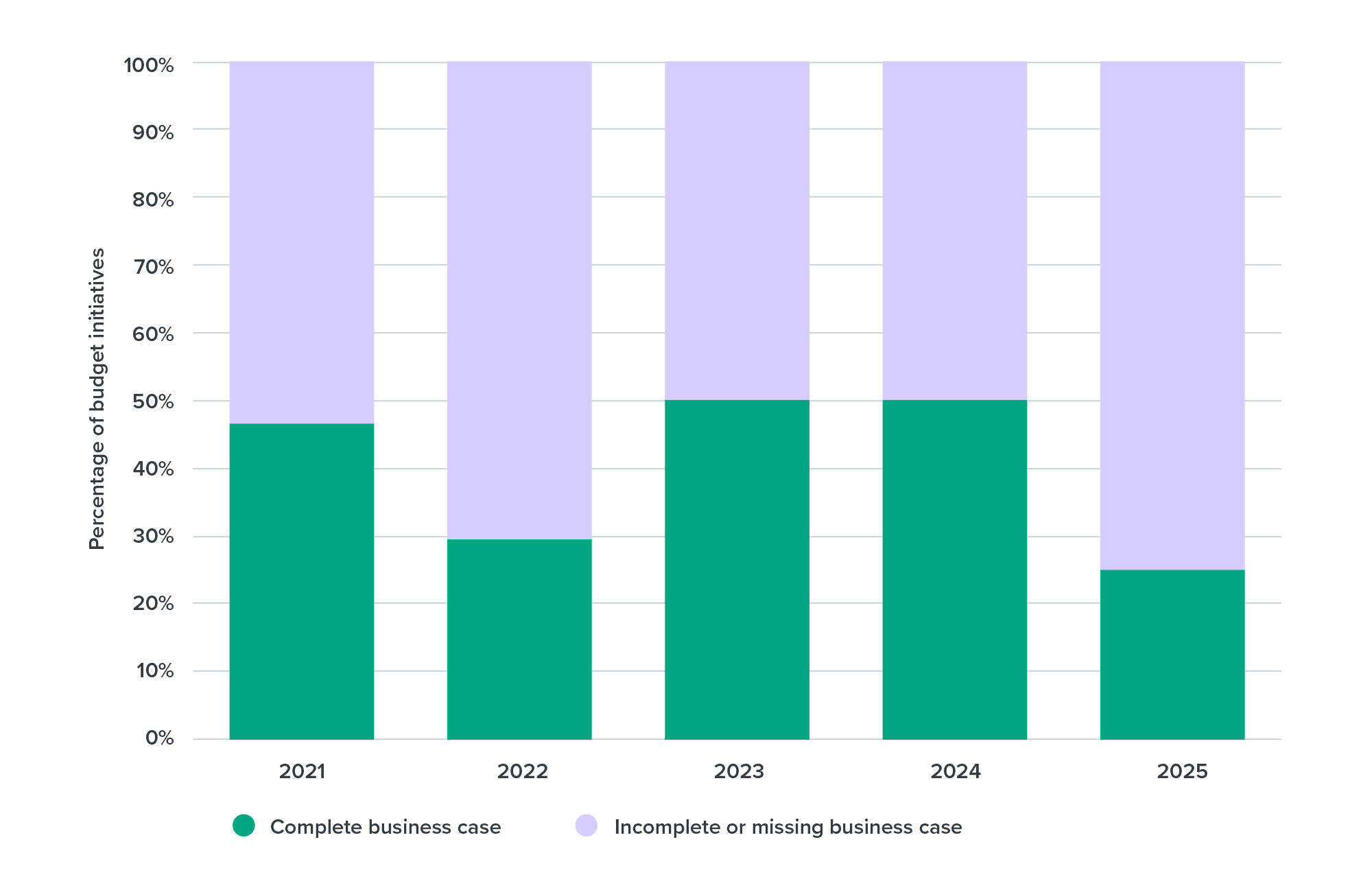

There is widespread non-compliance with core investment management standards. Agencies are required under a Cabinet Office circular to follow these rules, including the Better Business Case framework setting out a multi-stage planning process for major projects. Over the last five Budgets, half or less of the infrastructure-related initiatives assessed by the Treasury's Investment Panel had gone through a complete business case process before seeking funding (Figure 33). Less than a quarter typically provide cost-benefit analysis of their preferred option.102 The criteria used to assess Budget bids for new capital spending can also change from year to year, which makes it difficult for agencies to plan to consistent standards.103

Gateway reviews for high-risk projects are of limited use as investment advice. The reviews, which are required by the Treasury and carried out by independent experts, generally assume that a project will proceed, rather than testing whether it should. Because they are not conducted with Ministers as the primary client, they do not consistently provide clear advice on core considerations such as cost, value for money, deliverability, or investment readiness. Instead, Gateway reviews tend to focus on project-specific issues raised in internal interviews, making them more useful for the commissioning agency than for decision-makers.

Major projects carry outsized fiscal and delivery risks, yet decision-makers aren’t routinely getting robust independent assessments. The National Infrastructure Pipeline includes 44 megaprojects with expected costs of more than $1 billion, accounting for 52% of the total value of the Pipeline. Decisions on whether to progress projects of this scale will shape our ability to fund other priorities. Yet there is no mandated process to assess whether projects address the right problems, represent the most cost-effective options, or are ready to deliver. There is also limited public transparency. A review of 27 large public-sector projects found that key project documents, like business cases and assurance plans, were inaccessible more than half the time.104

Gaps in the assurance system are increasing the risk of bad outcomes. Deliverability problems for projects like New Dunedin Hospital and Scott Base aren’t being caught early enough, increasing the risk of cost escalations and delays. This undermines market confidence and delivery efficiency, as high-risk projects can be cancelled or significantly rescoped. The Treasury compiles information on significant investments through its Quarterly Investment Reporting, including budget and timeframe risks. But decision-makers may not have a fully informed view, as the agencies planning and delivering investments are often the ones providing information.

Half of all Budget bids typically have missing or incomplete business cases

Figure 33: Compliance with business case requirements among Budget infrastructure project funding bids reviewed by the Treasury’s Investment Panel from 2021 to 2025

Source: ‘Annual Report’. New Zealand Infrastructure Commission. (2024, 2025).

Strategic direction

Investment assurance is strengthened and consolidated within the Investment Management System (IMS)

Assurance functions should be brought together into a single agency. While the Treasury oversees the IMS, assurance functions are currently dispersed across central government. For example, the Commission runs the Infrastructure Priorities Programme (IPP), the Treasury provides Gateway reviews, and bespoke project reviews are conducted by multiple agencies. Having a single agency responsible for the system of ‘checks and balances’ would reduce duplication, allow for efficiency gains, and promote a consistent approach to investments as they move through different stages of planning and development. This will be even more important if an asset management assurance function is established.

Decision-makers would benefit from having a single ‘source of truth’. The consolidated assurance function should seek to establish clear and enduring minimum standards and assess agency capability to manage their assets and plan new investments. It should also provide objective analysis to support monitoring and advisory functions undertaken by agencies like the Treasury, the Ministry of Transport and the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development. Existing tools like Gateway would benefit from being reviewed to ensure decision-makers are getting the information they need to make informed funding decisions.

A consistent and high bar is needed for investment. It is difficult to track whether value for money and deliverability are improving over time because the Treasury’s Budget Evaluation Framework, which it uses to assess Budget bids for new capital investments, changes significantly every year. In future, a stable objective evaluation framework for investment proposals should be used, setting a high bar for value for money, and identifying projects that maximise the benefits achieved from investment under various possible scenarios. This need not preclude, and should inform, advice to Ministers on investment prioritisation tailored to the objectives and priorities of the Government of the day.

Completed projects should be assessed to help improve future planning and identify any system-wide issues. Information on past projects helps future projects learn how to replicate successes and avoid risks. The Gateway system, which originated in the United Kingdom, includes a step for reviewing completed projects to assess whether they delivered the intended benefits. New Zealand should consistently and transparently review completed major projects. This requires business cases to be preserved and made available, as well as data on project costs, completion dates, and benefits realisation.105

Asset management and investment plans and practices are reviewed to ensure they're working

Long-term asset management and investment plans need to be independently assessed. Agencies should develop these plans with a clear understanding of the condition and performance of their existing assets, and outline what additional infrastructure would be required and possible to deliver under different demand and funding scenarios. Under current settings, plans often lack sufficient supporting evidence and discussion of asset management practices. To lift quality and ensure consistency, the assurance system should independently assess these plans to confirm that proposed expenditure is justified and efficient. Agencies should also meet expected asset management standards, informed by best practice international principles.106

Budget decisions should flow directly from these long-term plans. When agencies seek funding for specific projects or programmes, they should be able to point back to their plans to show how proposals reflect demand pressures, emerging risks, or asset performance issues. This reinforces the value of long-term planning and ensures proposals are grounded in a coherent forward strategy rather than developed in isolation.

The assurance system should be strengthened to run the ruler over the asset management practices of capital-intensive agencies. Looking after existing assets and replacing them as they wear out should be a basic requirement for any infrastructure provider, yet the condition of many central government buildings and networks shows that this is not being consistently achieved. Agencies currently self-assess their own level of asset management performance. A dedicated assurance function – empowered to independently review asset management maturity against best practice international standards – would provide a far more reliable and comparable view of performance, particularly in high-value sectors such as health, defence and education.

Agencies with large portfolios of assets should be required to transparently report on how their infrastructure is performing. An independent assurance function should assess performance using standardised metrics, enabling comparisons across agencies and portfolios. As per new guidance from the Commission, reporting indicators should include cost, service and risk performance.107 For example, agencies should be able to say whether their actual and forecast spending on renewals is in line with depreciation, or report on the number of asset-related service failures in any given year.

Assurance is needed across all aspects of the asset management system. This will ensure agencies treat asset management as an essential business, not an optional compliance activity.108 New Zealand should learn from and utilise international best practice standards, and ensure agencies are supported to improve their internal capabilities.

Major projects and programmes receive consistent, independent assurance on readiness to invest

Decision-makers need consistent, independent assurance before committing to major projects. The scale of these projects means they can displace essential renewals and other priorities. Independent review helps guard against optimism bias, strategic misrepresentation, cost escalation, weak problem definitions, and pressure to proceed before credible options have been tested. It also strengthens delivery confidence by ensuring solutions match the scale of the problem.

Agencies should be supported to ‘think slow and act fast’ when planning new infrastructure projects. Good planning sets projects up for delivery success. Projects with robust business cases are less vulnerable to cost overruns, delivery delays, or later rescoping. Proper planning also ensures project options aren’t locked in and announced prematurely, and that low-cost and non-built solutions are properly considered. In Australia, the Grattan Institute found that prematurely-announced projects – announced prior to a full funding commitment or regulatory approvals – accounted for more than three quarters of cost overruns despite making up only a third of assessed projects.109

Project readiness should be tested at key stages in planning. High-quality assurance needs to occur at the stages with the greatest influence on outcomes: defining the problem, developing credible options, and selecting the preferred solution. The Treasury’s Better Business Case guidance provides these checkpoints, but reviews need to be applied more consistently and with greater rigour. Scrutiny of early-stage planning through Strategic Assessments and Indicative Business Cases is particularly important as these stages determine whether major projects proceed, are rescaled, or are set aside. Review at the Detailed Business Case stage is needed to confirm that the right solution is being funded.

Projects should be reviewed against standard criteria that enable comparison and prioritisation. Existing tools offer useful checks, but their scope varies and they do not apply a common set of criteria across all proposals. International best practice is to assess projects against a consistent framework for strategic alignment, value for money, and deliverability.110 Applying this consistently would give Ministers a clearer basis for comparing options, identifying risks and prioritising investment. There is a need to improve practices to help ensure the right projects are progressed.

![]()

Box 3

Insights from two rounds of the Infrastructure Priorities Programme

The Infrastructure Priorities Programme (IPP) highlights where project planning needs to improve. The Commission has assessed over 120 voluntary applications using the standardised investment-readiness tool. As well as providing an endorsed ‘menu’ of projects and problems, the results show recurring gaps in strategic assessment, option development, value for money testing, and delivery planning. Strengthening these areas will help ensure projects are proportionate and ready to deliver once funding is confirmed.

Stronger analysis of problems or opportunities is needed

Good project planning begins with a precise, evidence-based understanding of the ‘size of the prize’. Clear problem definition anchors the business case: it drives option development, guides proportionate responses, and ensures investment decisions are grounded in need. Across two IPP rounds, applicants identified valid needs but often struggled to define or size the specific problem, making it harder to match solutions to underlying demand.

A stronger focus on cost-effective, best-value solutions is required

Planning should prioritise the best-value solution, not the most complex one. This means considering a full range of credible options, including staged, non-built and low-cost interventions, testing them with tools like cost-benefit analysis, and timing major investments so they enter service when demand justifies them. Strong option development and value for money testing are essential for managing portfolio affordability.

Many business cases converge too early on a preferred solution. Subsequent analysis is sometimes used to defend a preferred solution rather than to test it, increasing the risk of choosing the wrong approach.

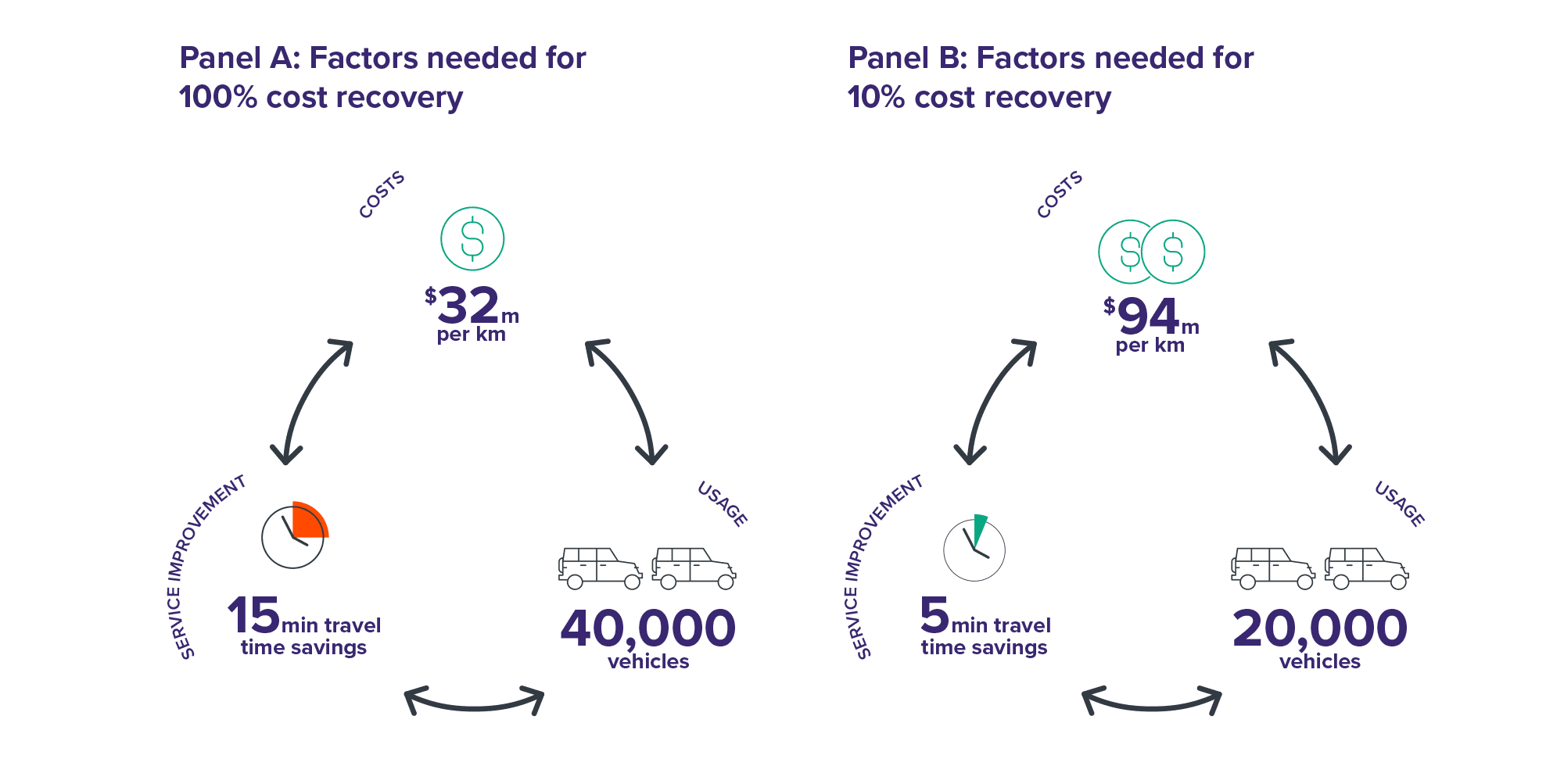

Higher-quality projects also expand funding choices. The Commission’s analysis shows that projects delivering high benefits to many users at an affordable cost are far more likely to recover a meaningful share of their costs through revenue tools like tolls (Figure 34). Only a small subset of projects can self-fund, but stronger value for money discipline improves both investment decisions and funding pathways.

Figure 34: Predicted cost recovery for new toll roads

Source: New Zealand Infrastructure Commission modelling 111

Projects should set themselves up for delivery success

Strong deliverability planning underpins successful major projects. Deliverable projects start with clear governance, capable leadership, early identification of cost and scope risks, and sound understanding of market and workforce conditions. Planning for implementation must begin early so procurement strategy, design and timing reflect real-world constraints.

Project delivery ultimately depends on agency capability. Business cases offer a window into an agency’s delivery readiness, but can only reveal so much. Delivery performance reflects whether agencies have the governance, skills and commercial judgement to make timely decisions and manage risk. Strengthening this capability is essential to improving deliverability.

Planning provides options for responding to shifting Government objectives

Good infrastructure planning gives the Government genuine choices. Different Governments have different investment priorities, but project fundamentals like value for money and deliverability remain essential regardless of changing policy goals. Stronger assurance functions that lead to a diversified ‘menu’ of high-quality proposals will allow the Government of the day to respond to emerging needs, rebalance regional investment, and pursue different mixes of economic, resilience, social, and environmental outcomes without starting from scratch each time.

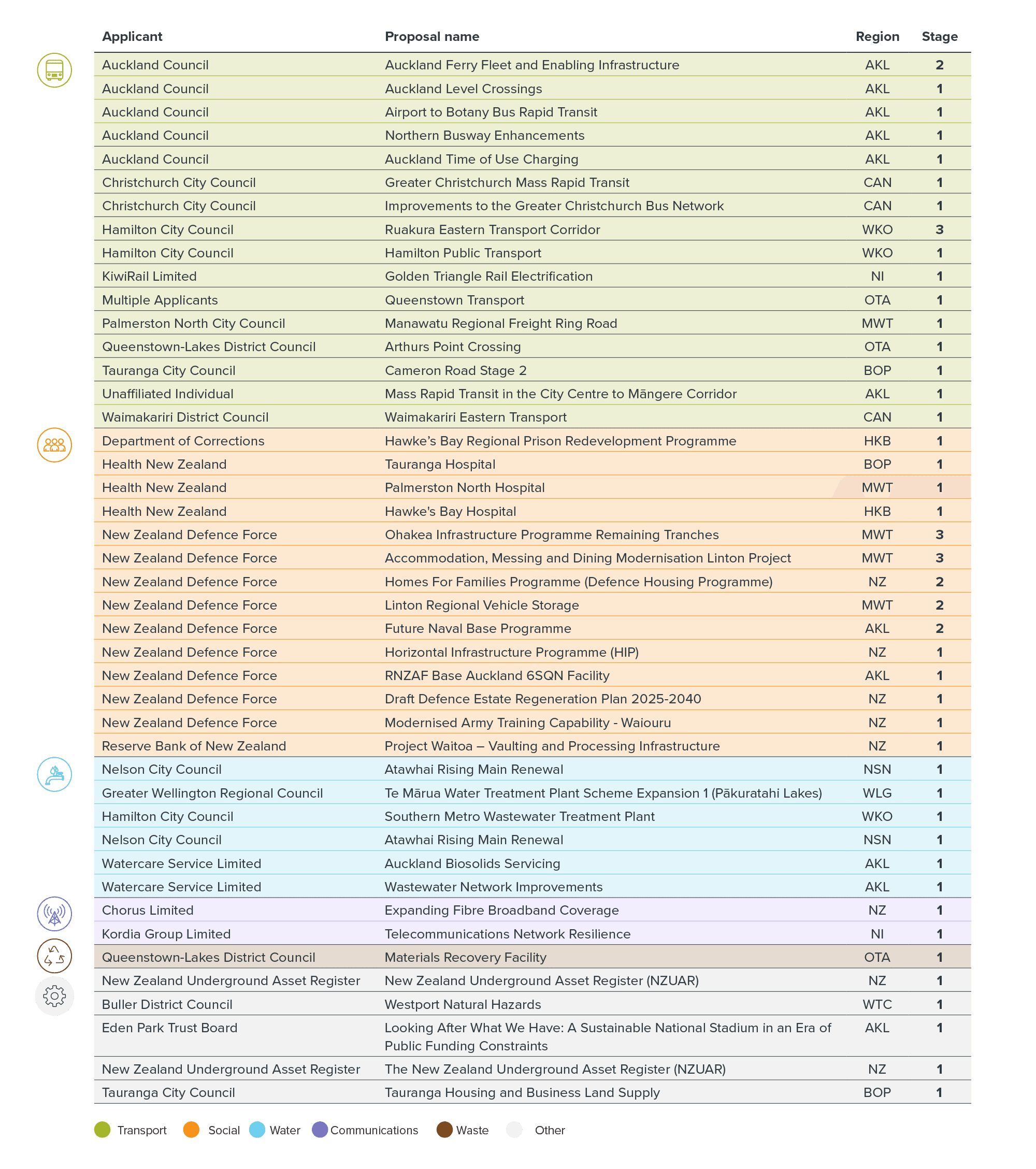

Two rounds of the Infrastructure Priorities Programme show this is achievable. We have endorsed a broad set of proposals across regions and sectors that meet core tests of strategic alignment, value for money, and deliverability (Figure 35). Together, they demonstrate the range of credible choices available: proposals that improve regional freight connectivity, strengthen urban public transport, expand telecommunications resilience and coverage, renew the defence estate, enhance water services, and manage waste more sustainably. This approach can give current and future Governments the flexibility and confidence to pursue their objectives with investment-ready projects.

Project planning offers alternatives for responding to different objectives

Figure 35: IPP endorsements from rounds 1 and 2

Note: IPP proposals can be endorsed at one of three stages. Being endorsed at stage one means an applicant has identified a priority opportunity or problem that is ready to be explored in an indicative business case; endorsement at stage two means applicants have identified a shortlist of possible solutions, including low-cost options and can proceed to a detailed business case; being endorsed at stage three means an applicant has identified a preferred solution and has a detailed business case that is ready to seek funding.

![]()

Recommendation 7

System-wide assurance

Establish a consolidated assurance function that provides Ministers with a system-wide view of infrastructure planning, delivery, and asset management performance and risk.

Implementation pathway

This could be implemented by:

- Integrating existing and new assurance mechanisms into a single Investor Assurance Function located in a single government entity.

- Reviewing and standardising assurance products and reporting formats.

- Ensuring the function has dedicated funding and that advice is independent of proponents.

- Providing Ministers with consolidated system-wide reports on planning, delivery, and performance.

Responsible agencies

The Treasury for policy work, agency responsible for the infrastructure investor assurance function to be determined

Timeframe

Consider through CO (23) 9 refresh.

![]()

Recommendation 8

Asset management assurance

Establish an assurance function for capital-intensive central government agencies covering asset management and investment planning activities.

Implementation pathway

Following implementation of long-term asset management and investment planning requirements, this could be implemented by:

- Establishing a new asset management assurance function for central government agencies, which would review agency asset management and investment plans and performance against these plans.

- Developing a standard methodology for assessing plans and performance.

- Embedding requirements for independent assurance of plans and performance.

Responsible agencies

The Treasury for policy work, agency responsible for the asset management assurance function to be determined

Timeframe

Consider through CO (23) 9 refresh.

![]()

Recommendation 9

Investment readiness assurance

Strengthen investment assurance by applying a transparent, independent readiness assessment to major Government-funded investment proposals.

Implementation pathway

This could be implemented by:

- Mandating participation in the Infrastructure Priorities Programme for major Crown-funded proposals.

- Use results of Infrastructure Priorities Programme assessments in the Treasury’s advice to Government through the Investment Management System and Budget.

Responsible agencies

The Treasury for policy work, New Zealand Infrastructure Commission for IPP

Timeframe

Consider through CO (23) 9 refresh.