Content

Content

Draft National Infrastructure Plan

7.4. Electricity and gas | Te hiko me te haurehu

7.4.1. Institutional structure

Service delivery responsibilities

- This sector includes electricity transmission, distribution, generation and retail, and ‘downstream’ gas transmission, distribution and retail. However, it excludes liquid fuels (e.g. petrol and diesel) and ‘upstream’ gas production and processing activities.

- Electricity infrastructure and services are provided by commercial entities, some of which are fully or partly owned by central or local government. Government is the majority shareholder of three generation companies (Genesis, Meridian, and Mercury) and the transmission provider (Transpower). There is a mix of private and local trust ownership of the distribution companies. There are a number of electricity retail companies, some of which also generate electricity.

- Gas infrastructure and services are provided by commercial entities. Gas transmission and distribution companies operate as regulated monopolies. There are several gas retail companies.

Governance and oversight

- The Electricity Authority oversees and regulates the electricity sector, including the electricity wholesale and retail markets. The Commerce Commission regulates electricity and gas networks, including electricity distribution businesses, gas pipeline businesses and Transpower, and investigates potential breaches of competition law.

- Competition exists at the retail level, with four major retailers and over 30 smaller businesses selling electricity to consumers.

- The ‘downstream’ gas sector is co-regulated by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) and the Gas Industry Company.

- MBIE provides policy stewardship for both the electricity and gas sectors.

7.4.2. Paying for investment

- Electricity services are customer-funded. All costs of generating, transmitting, distributing and retailing electricity (along with the cost of purchasing carbon emissions units through the Emissions Trading Scheme) are passed through to customers based on the volumes bought, sold and used.

- Electricity generators sell into a competitive wholesale market or direct to industrial customers through power purchase agreements. Locational marginal pricing in the wholesale market helps signal opportunities for investment in additional capacity.

- Direct central government financial support for electricity and gas infrastructure is rare but financial support, such as the Winter Energy Payment, is available for some households.

7.4.3. Historical investment drivers

- Investment in electricity networks peaked from the 1950s through 1980s, as New Zealand added significant capacity to the network. Investment responded to technological innovation requiring more electricity usage, industrialisation, and population growth.

- In recent decades, growth in demand for electricity investment has been relatively subdued. Gas supply and demand have declined, due to slowly depleting gas reserves and declining investment.

- Investment to meet demand growth for electricity and gas is driven by factors like population growth, shifting technologies around energy usage (such as electric vehicles) and commercial/industrial usage.

- In electricity, other investment occurs to meet peak demand or provide resilience against outages, but also to ensure consistent supply and prices.

- New Zealand’s legislated net-zero carbon emission goals and broader energy market policy settings impact both gas and electricity investment.

7.4.4. Community perceptions and expectations

- In general, New Zealanders’ expectations for the reliability of electricity seem to be well met.

- However, there is a general perception that the prices users pay are higher than the costs to supply.

- New Zealanders are increasingly concerned about the electricity sector’s ability to ensure electricity supply will be sufficient in the future.

- Most New Zealanders support electricity charges that are based on usage.

7.4.5. Current state of network

New Zealand’s difference from comparator country average

|

Network |

Investment |

Quantity of infrastructure |

Usage |

Quality |

|

Electricity |

-3% |

+23% |

-46% |

-12% |

Comparator countries: Columbia, Costa Rica, Chile, Canada, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden. Similarity based on: Income, population density, terrain ruggedness, urban populations, energy exports, heavy industry share of GDP. Percentage differences from comparator country averages are based on a simple unweighted average of multiple measures for each outcome. Further information on these comparisons is available in a supporting technical report.[109]

- Our electricity networks are somewhat unique relative to other countries. We have a comparatively large transmission network, reflecting long distances between our generation and usage, and no grid interconnections with other countries.

- Investment levels are about average compared to our peers.

- Outages in New Zealand appear to be more frequent in number and duration than peer countries and are among the highest in the OECD. However, electricity generation in New Zealand produces very low emissions relative to the OECD average and comparator countries.

- The Commission also publishes performance dashboards that can be used to understand changes in the performance of New Zealand’s energy sector over time.[110]

7.4.6. Forward guidance for capital investment demand

|

Electricity and gas |

2025–2035 |

2035–2045 |

2045–2055 |

2010-2022 historical average |

|

Average annual spending 2023 NZD) |

$6.0 billion |

$6.7 billion |

$7.9 billion |

$2.4 billion |

|

Percent of GDP |

1.4% |

1.3% |

1.4% |

0.8% |

This table provides further detail on forward guidance summarised in Section 3. Further information on this analysis and the underlying modelling assumptions is provided in a supporting technical report.[111] Note: This table was updated on 24 July 2025.

- Meeting our legislated net-zero carbon emissions goals will require a meaningful uplift in electricity investment over the next 30 years. This will include a need for new electricity generation, transmission, distribution, and ‘firming’ generation to supplement variable renewables like wind and solar.

- Over the 30-year period, based on Climate Change Commission scenarios, we estimate that this will require approximately $24 billion worth of capital investment above baseline demand driven by population and income growth, or just over $700 million a year on average. Most of this investment (90%) will be in new generation, and the remaining will be in the transmission and distribution network.

- Most of this investment is front-loaded in the next 10 to 15 years; however, we will also have to account for added renewal spending in the second half of the forecast period.

- Without decarbonisation-related investment, we expect that investment in electricity networks will largely track the more subdued investment trends of the past 20 years. This is because other demand drivers such as population and economic growth are expected to be relatively modest, although resilience investment is likely to be an increasing focus.

7.4.7. Current investment intentions

- Electricity and gas investment has been stable in recent years but current market information suggests that it may rise in future years. Realisation of increased investment will depend on market factors, including consumer demand for more electricity, as well as policy factors like the consenting environment.

- Investment intentions submitted to the Pipeline largely reflect distribution and transmission networks. As a result, the Commission has worked with the Electricity Authority to include a view of generation investment intentions from their augmented 2023 survey of generators (reflected in a 13 year span). We have excluded some speculative offshore wind investment in the mid-2030s from this analysis. We expect to provide updated information in the Final Plan.

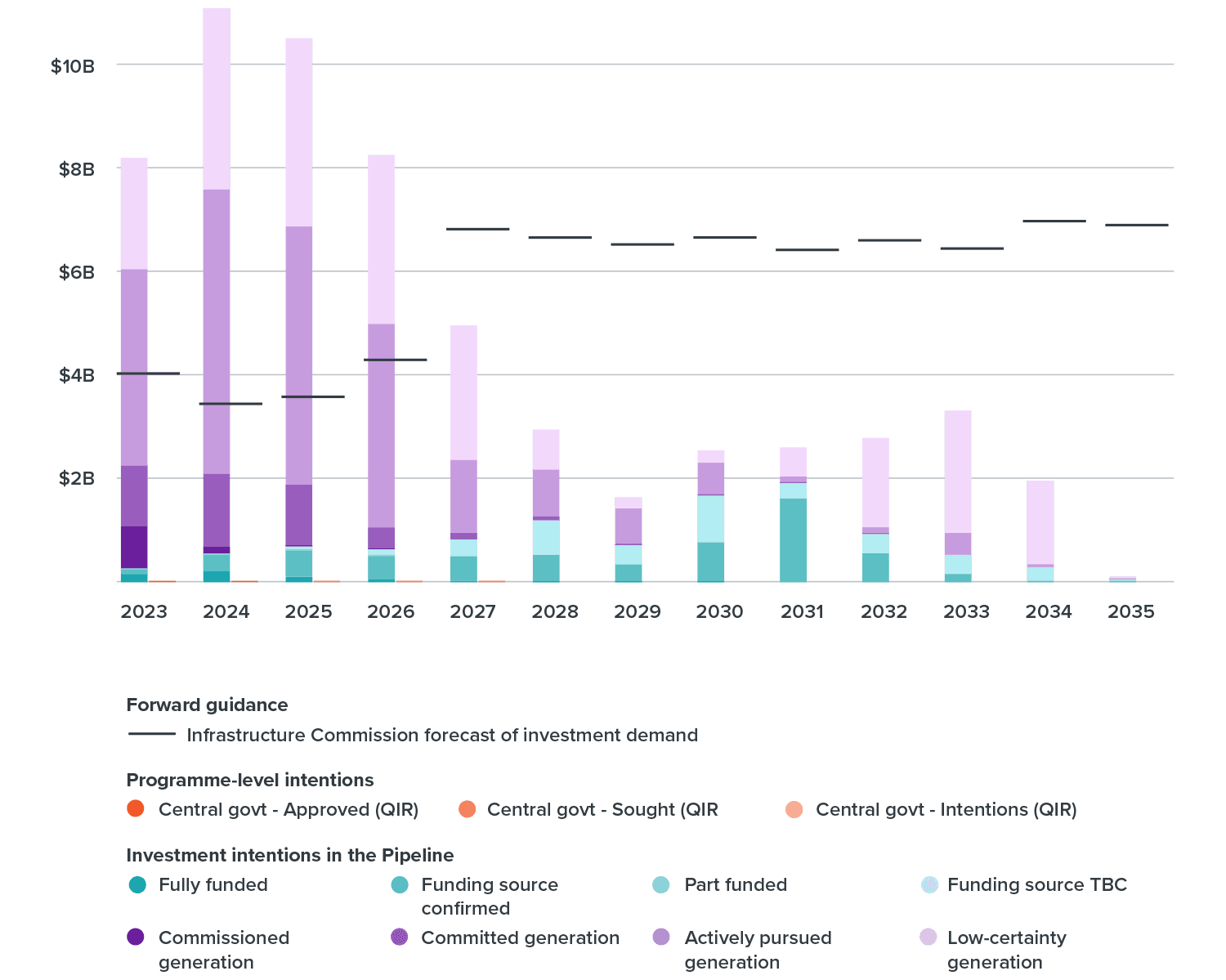

- The following chart shows that projected spending to deliver initiatives in planning and delivery in the Pipeline (blue bars) and the Electricity Authority’s generation investment intentions survey (purple bars) is expected to be significantly higher than the Commission’s investment demand outlook (black lines) in the next few years, but lower beyond this.

- Current intentions in the Pipeline account for around 14% of the Commission’s modelled investment demand over the next 10 years, while 2023 generation investment intentions from the Electricity Authority account for a further 48%. This indicates either a relatively short planning horizon for electricity investment, or uncertainty about future demand growth.

This chart compares two different measures of future investment intentions with the Commission’s forward guidance on investment demand. The blue and violet bars show project-level investment intentions from the National Infrastructure Plan and the Electricity Authority’s generation investment survey, distinguishing based on funding status.

The orange bars show the small amount of energy-related investment intentions in central government’s reporting to the Treasury’s Investment Management System. The black lines show the Commission’s forward guidance on investment demand.

7.4.8. Key issues and opportunities

- Pricing: The energy transition may require network investment ahead of demand to facilitate decarbonisation. Pricing approaches will need to consider investment risk and affordability for users during the transition period. Affordability and reliability of energy could in turn affect economic outcomes for energy-using industries and the pace at which households and businesses convert from fossil fuels to electricity.

- Coordination: Electricity is expected to play a major role in meeting our 2050 legislated emissions goals. Coordination between increased investment in generation, transmission distribution and distributed energy resources (for example, home solar and batteries) will be required.

- Governance: While economic regulation has worked well for transmission and distribution providers, perceptions among the public indicate low confidence in prices reflecting costs. Improving transparency around investment intentions may help improve this.

- Efficient regulation: Accommodating new generation, network expansion and distributed energy will require enabling resource management direction.

- Policy certainty: Policy uncertainty may continue to have an impact on future electricity demand. These include policies related to the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), the government’s role in managing dry-year risk, and other complementary policies such as the former Clean Car Discount. Long-term decline in gas supply and demand will require gas distributors and users to adapt, which may mean adopting emerging technologies (e.g., hydrogen or biogas) or demand management options.