Content

Content

Draft National Infrastructure Plan

4.3. Use fit-for-purpose pricing and funding tools | Whakamahia ngā utauta utu me te whiwhi pūtea whaitake

4.3.1 Context

Pricing and funding settings determine what resources are available to build, maintain, and operate assets. When working well, these settings should enable infrastructure providers to invest sufficiently to meet long-term user demands, while discouraging unaffordable spending.

These settings also help to maximise the benefits we achieve from infrastructure networks. For example, time-of-use charging for congested urban road networks encourages people to travel during less congested times or to take public transport instead, speeding up traffic and increasing the efficiency of the overall transport network.

Pricing and funding approaches vary throughout the infrastructure sector. They are guided by different legislation and subject to different decision-making processes. Central government does not directly set prices for many types of infrastructure, but its policy choices often affect how other infrastructure providers can fund themselves. Ongoing work is needed to ensure that pricing and funding approaches are fit for purpose.

4.3.2. Strategic directions

Pricing and funding tools are optimised for different infrastructure services

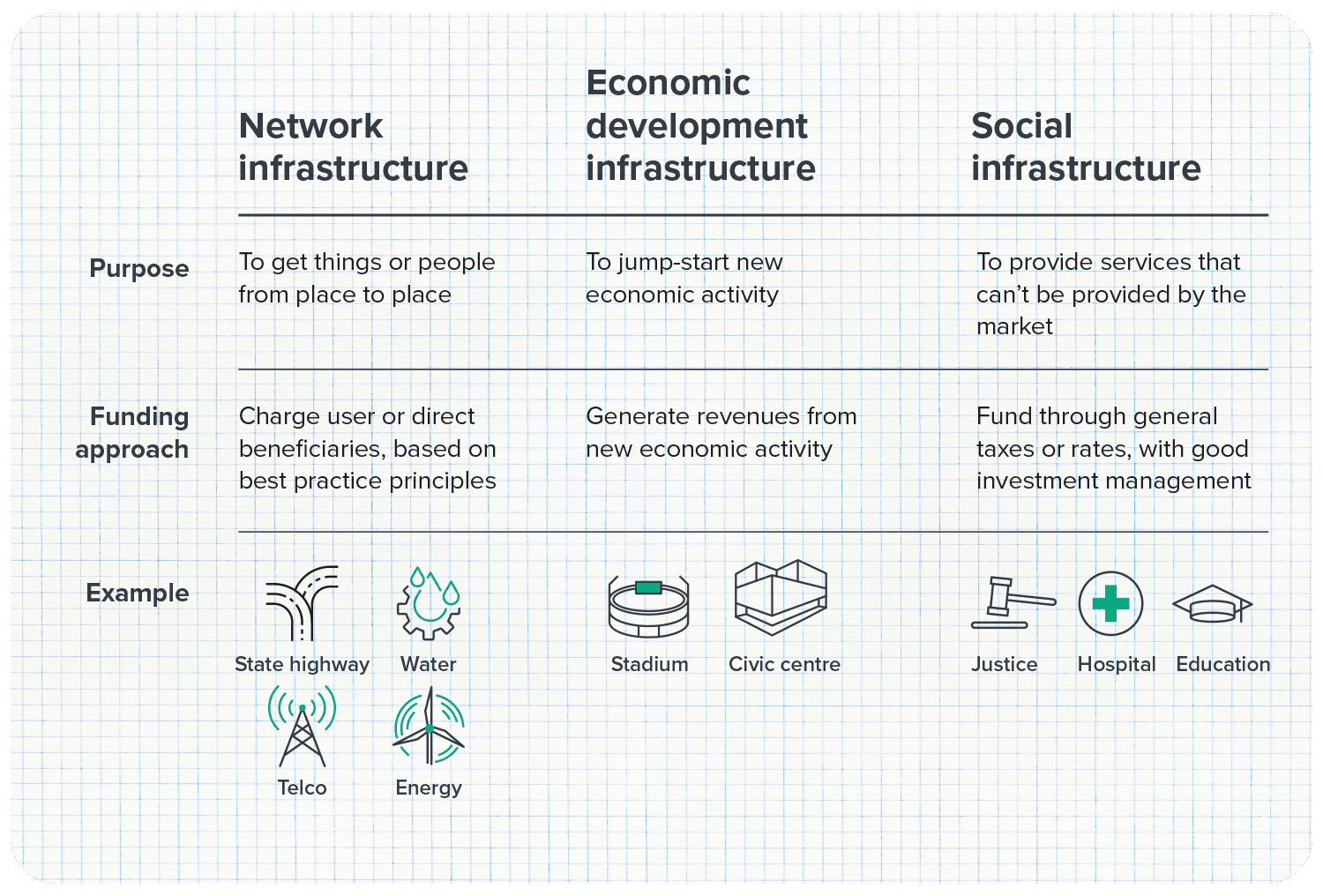

Pricing and funding approaches should ensure we get enough investment in all sectors. However, the right approach is different in different sectors, depending upon the types of services that they are providing (Figure 22).

We differentiate infrastructure services that can pay for themselves and those that cannot. Network infrastructure, like transport, water, electricity, and telecommunications, is different from social infrastructure, like schools, hospitals, courts, prisons, public parks and open spaces, and the defence estate.

Network infrastructure should fund itself by charging people who use the infrastructure or directly benefit from it. This is because most of the benefits of network infrastructure flow to the people who use the network. This doesn’t necessarily mean that every piece of a network needs to ‘pay its own way’. For instance, some roads might return less in user revenues than they cost to maintain, and urban public transport services might require cross-subsidies from other transport users. It is appropriate for some parts of a network to subsidise where there are broader benefits or equity considerations exist. But the network should cover its costs.

Social infrastructure generally needs to be funded from general taxes or local government rates. This results in more consistent and equitable access to services, like education and healthcare, that are needed to participate in society.[55] In other cases, like courts, prisons, and Defence estate, social infrastructure provides broad benefits to society, rather than to the people who are directly using it. For instance, court infrastructure helps provide confidence in the rule of law. However, public funding of these services does not always imply public ownership of the infrastructure assets, because it is sometimes more cost effective to lease assets or contract others to provide services.

Economic development infrastructure should generate enough revenue to pay for itself. This is not a well-defined type of infrastructure but it includes projects like convention centres, business accelerator precincts, and stadiums that are intended to jump-start new economic activity. Revenue generation is essential for economic development infrastructure because it provides a ‘market test’ of whether it will succeed in growing the economy. Revenues could be earned directly from users or indirectly through levies or charges on wider beneficiaries. For example, Wellington’s Sky Stadium earns revenues from ticket sales and from a targeted rate levied on nearby businesses that benefit from additional visitor activity, and Eden Park Trust (Auckland) can cover operating costs (although not depreciation on its existing assets) through ticket sales.

When network infrastructure and economic development infrastructure is better at funding itself, more money is available to invest in social infrastructure. Central and local government have limited tax and rate revenue for investment, so when the cost to provide roads and stadiums spills over into general tax or rate revenues, less is available to invest in schools, hospitals, parks and other social infrastructure.

Source: New Zealand Infrastructure Commission. (2025).

Figure 22: Pricing and funding approaches for different types of infrastructure

Users or direct beneficiaries pay the full cost of network infrastructure

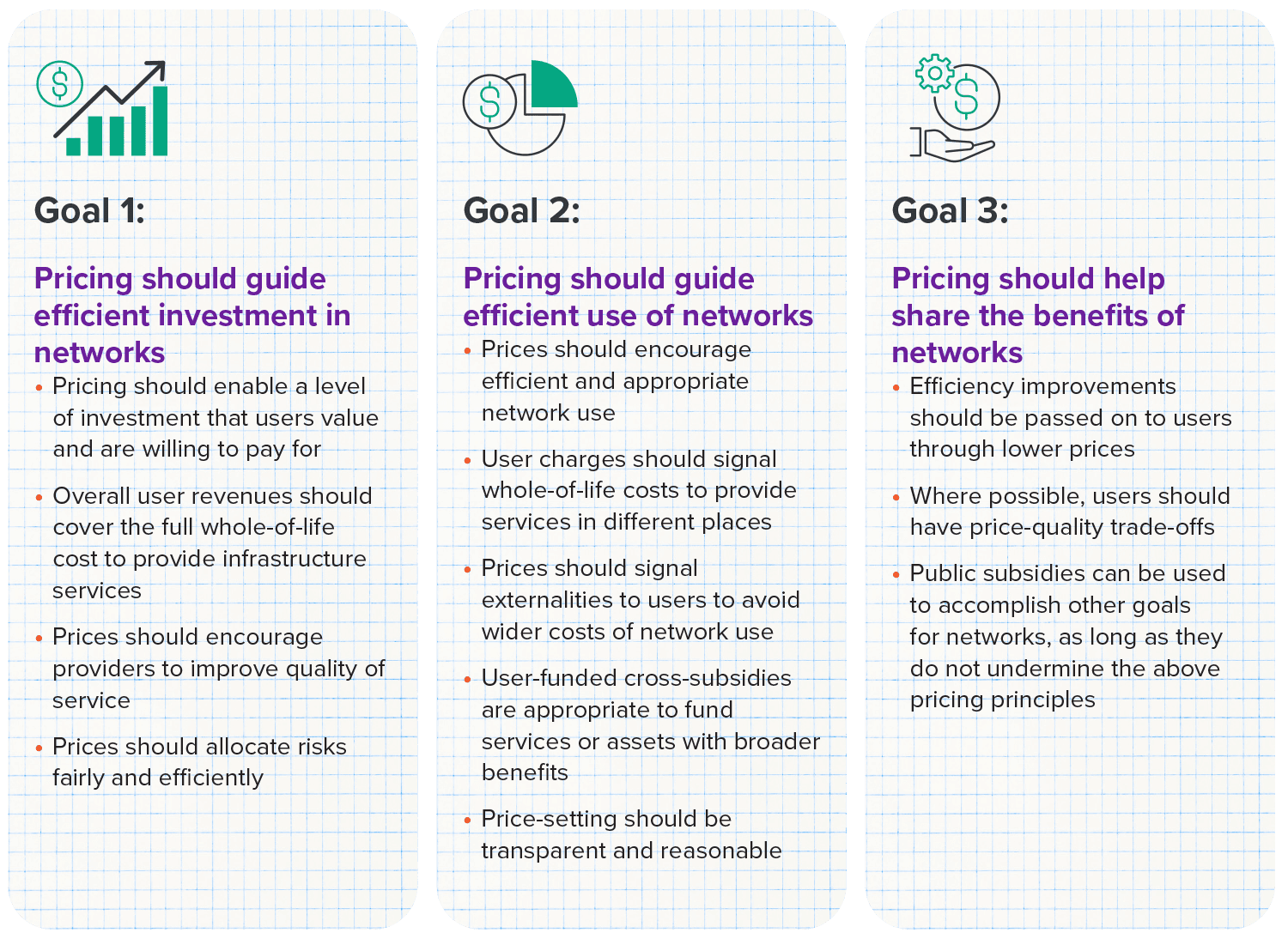

Network infrastructure should be priced to achieve three main goals (Figure 23). The first is that user revenues should pay the full cost of providing infrastructure and services. This is important for ensuring that we can provide and maintain the infrastructure we need. The second is that prices should encourage people to use networks efficiently, resulting in high use but discouraging excessive congestion. The third is that pricing should be used to share the benefits of networks widely through society, once the other two goals have been achieved.

When more investment is needed, it should be funded out of increased user revenues. This could be done by increasing existing charges, introducing new charges (like tolling new roads), or investing in ways that increase usage and thereby bring in new revenue from existing charges.

Sectors with good pricing practices are better able to raise funds for maintaining and improving assets

Source: Adapted from ‘Approaches to Infrastructure Pricing Study: Part 2 – Current Pricing Analysis’. PwC. Report for the New Zealand Infrastructure Commission. (2024).

Figure 23: Best-practice principles for network infrastructure pricing.

Multiple ways can be used to charge users or direct beneficiaries. These include charges paid at the point of use, like fuel taxes, public transport fares and electricity supply charges, and charges for access to the network, like development levies on new houses and fixed monthly charges for mobile phones. How we choose to price networks can affect how people use those networks and how the costs of investment are distributed between different users, for instance between low-income and high-income households. When considering new capital investment, broad resistance to increased network charges may suggest that most users do not think project benefits are proportionate to project costs.

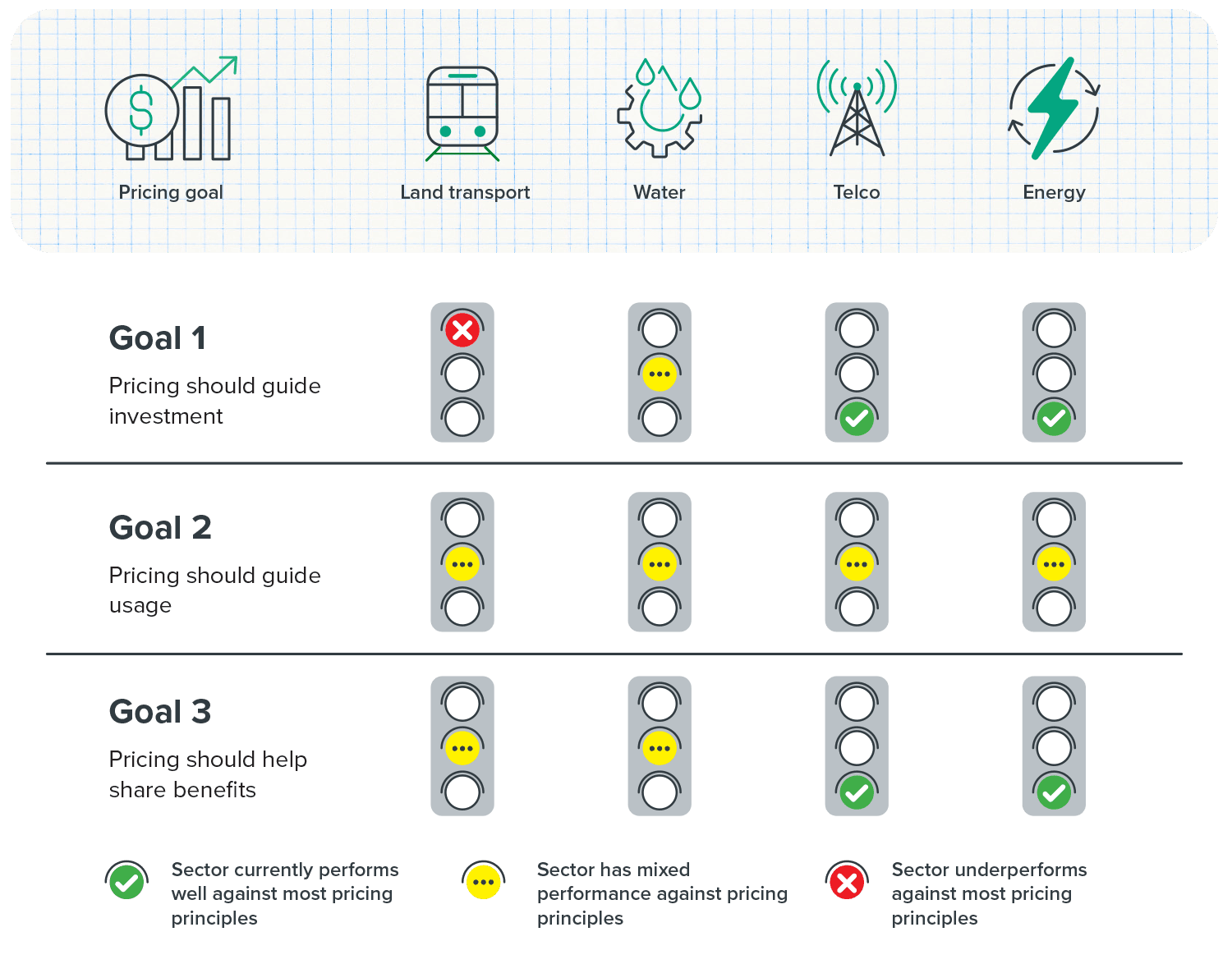

Energy and telecommunications infrastructure performs well against these goals, while land transport and water pricing needs to improve (Box 9). The need is ongoing for improvement to pricing practices, especially for land transport and water.

Source: ‘Approaches to Infrastructure Pricing Study: Part 2 – Current Pricing Analysis’. PwC. Report for the New Zealand Infrastructure Commission. (2024).

Figure 24: Performance against best practice goals by sector.

Box 9

How network infrastructure sectors are performing against pricing goals

A 2024 study of infrastructure pricing found that practices for electricity and telecommunications networks are generally well aligned with network pricing goals (Figure 24). These sectors predominantly collect their revenue through direct user charges and operate within market structures and policy settings that support good pricing. By contrast, land transport and water pricing does not perform as well against these goals.

For instance, most road transport users do not pay directly for the transport services they use, disincentivising efficient use. While opportunity exists for transport pricing to demonstrate where road users value services, investment decisions are typically driven by policy rather than price signals. This arrangement contributes to transport investments exceeding demand (Box 8).

Historically, a council’s water service costs and revenues could be pooled with those of other council services, making financial and service performance difficult to measure. The costs of delivering water services are directly influenced by the volume of water collected, treated and distributed to users. But when revenue is collected through local government rates, users have limited visibility of the water services they use, the cost of those services and the extent of cross-subsidisation between users.

Pricing practices are improving

Councils are increasingly moving toward water metering and volumetric charging. This pricing practice incentivises conservation and leak reduction. It also helps councils defer the need for expensive capital upgrades. Current water sector reforms are setting requirements for financial sustainability, which in turn should encourage service providers to consider pricing models that better align with best-practice principles.

Similarly, the introduction of ‘time-of-use’ charging legislation is an important step in enabling the use of pricing to encourage trips at less congested times of day. Tolling reform also provides opportunities for greater use of tolls to demonstrate where road users value additional capacity.

Financing tools spread the upfront costs of investment

Once appropriate pricing and funding methods are in place, infrastructure providers should consider options for financing the upfront costs of investment. Funding represents all the money needed to pay for infrastructure, which can come from users, taxpayers and ratepayers. Financing is about when we pay for infrastructure. It could mean using cash surpluses now or borrowing and repaying later. Financing is about how we align the timing of revenues from an infrastructure asset to repay the money needed to build it.

Many financing options are available. The Treasury’s ‘Funding and Financing Framework’ encourages consideration of all options.[56] These range from comparatively simple options, like taking out bank loans or issuing government bonds, through to more complex options like establishing special purpose vehicles or public private partnerships to finance projects. Infrastructure providers can also raise cash for investment through ‘asset recycling’, which means selling existing assets to free up money to buy new ones. Increasingly, iwi entities are seeking a role in financing and owning infrastructure, through a range of mechanisms.

Central and local government infrastructure providers can seek support for complex financing options. National Infrastructure Funding and Financing Limited is central government’s centre of expertise on funding and financing. It provides specialist expertise in public private partnerships and special-purpose financing transactions under the Infrastructure Funding and Financing Act 2020.

4.3.3. Recommendations

Appropriate pricing and funding tools are required for all infrastructure sectors. We make one recommendation to address this. The first speaks to what is needed across all infrastructure sectors as well as best practices for network infrastructure pricing. In Section 5, we make further recommendations aimed at ensuring that central government accurately forecasts what is needed for social infrastructure that is funded through the Budget.

These recommendations are important to ensure that infrastructure providers are able to invest the right amount in existing and improved assets to meet future demands.

Recommendation 6

Funding pathways: Funding tools are matched to asset type (user-pays for network infrastructure, commercial self-funding for economic-development assets, and tax funding for social infrastructure) to keep the overall capital envelope affordable. User-pricing principles are applied across all network sectors so user charges fully fund investment, guide efficient use of networks and distribute the benefits of network provision.

This recommendation would need to be implemented through policy and operational changes, which we are investigating further. To address identified issues with land transport and water pricing, we expect implementation to include volumetric charges for water use, time-of-use charging on transport corridors and, where appropriate, value capture levies to help pay for investment with broader beneficiaries.