Content

Content

Draft National Infrastructure Plan

4.2. Establish sound governance and oversight for all sectors | Te whakarite i te mana urungi pakari me te tirohanga mō ngā rāngai katoa

4.2.1 Context

Governance is about aligning decision-making with the long-term interests of those using and paying for infrastructure. Oversight arrangements should provide transparency of infrastructure providers’ performance. They should also establish incentives to invest in and operate infrastructure in ways that benefit those who use and pay for services. Good governance requires providers to engage with users and collect information about their long-term interests. This includes their preferences, expectations, priorities and needs, as well as what they are willing to pay for.

Various governance and oversight arrangements are in place across the infrastructure system. Central government, local government and commercial entities all have different oversight and accountability arrangements. These include legislative frameworks governing infrastructure providers, roles for sector regulators, transparency and consultation requirements, and audit and financial oversight rules. The work to ensure that infrastructure governance works well and enables us to identify and meet our infrastructure needs in a timely and consistent way requires ongoing attention.

4.2.2. Strategic direction

Effective oversight for all infrastructure sectors

Oversight mechanisms are needed in all infrastructure sectors, although the details can vary. In the absence of oversight mechanisms, infrastructure providers that do not face competition may not act in the long-term interests of infrastructure users. Depending on the context, this can result in overinvestment (where infrastructure providers charge users more than they would prefer to pay to build infrastructure that is not valued by users), under-investment (where infrastructure providers spend less on their assets in order to use revenues for other purposes), or misinvestment (where infrastructure providers do not succeed in investing in the types of assets or services that are most valued by users).

Oversight mechanisms are already in place for most types of infrastructure (Table 4). All infrastructure providers are governed under some form of overarching legislative framework, although the legislation varies. They all face audit requirements for their financial reporting. Many require financial oversight due to the need to borrow money through financial markets. All sectors must comply with cross-cutting regulation, such as the Health and Safety at Work Act 2015, or resource management consenting.

Central government, local government, and commercial entities have different governance. Central government and local government are both governed by elected representatives accountable to voters. By contrast, commercial entities are governed by boards accountable to shareholders. Many commercial entities also have regulatory oversight of their expenditure and service quality, for instance through the Commerce Commission, and local government water infrastructure is entering this regime. The Māori Crown relationship is also an important aspect of the operating environment that we discuss further below.

Performance information should be transparent and accessible to people who use and pay for infrastructure. Transparency is needed to drive accountability. As a result, oversight mechanisms often require that relevant information on performance and spending is publicly available. Examples include the Commerce Commission’s information disclosure regime for regulated sectors, information on electricity market performance published by the Electricity Authority, and spending and asset disclosures required by the Local Government Act 2002. For infrastructure provided by central government, the Public Finance Act 1989 provides the main framework for transparent reporting by central government agencies and the government as a whole.

Infrastructure providers should act in their consumers’ interests. One way to do this is through pricing models that incentivise them to provide infrastructure services that users value. Another approach is through consultation with users. Local governments are legally required to undertake public consultation before making decisions. Sector regulators like the Electricity Authority must also meet consultation requirements when making rules. In New Zealand, some infrastructure providers use participatory approaches to involve users directly in decision-making on complex topics. Examples include a community panel approach to considering congestion charging in Auckland[43] and a citizen’s assembly to make decisions around the long-term future of Auckland’s water supply.[44]

Governance looks different for central government, local government, and commercial entities

Note: ‘Commercial entities’ includes some organisations that are owned by central or local government but run on a commercial basis, like council-controlled companies, state-owned enterprises and mixed-ownership model companies, as well as some organisations that are run commercially but not for profit, like electricity distribution businesses owned by consumer trusts.

Table 4: Oversight and accountability mechanisms for different types of infrastructure

Māori-Crown relationships

The environment within which Māori and infrastructure providers engage on infrastructure initiatives is inherently diverse, fluid and complex.[45]

While there is ongoing discussion regarding what the Treaty / Te Tiriti requires, there appears to be consensus between mana whenua groups, the New Zealand courts and infrastructure providers that (whatever else it does or does not require) the Treaty / Te Tiriti obliges both Māori groups and government infrastructure providers to:

- act reasonably, honourably and in good faith, and be genuine, collaborative, and respectful

- listen to what others have to say, consider those responses and then decide what will be done.

Early, enduring partnerships are important for good outcomes (Box 7). This includes working with iwi and other Māori groups to build capability before it's needed, providing clarity of roles early, making project information accessible to Māori groups, and recognising Māori groups’ mātauranga (knowledge) as a factor that can add value to projects.

Box 7

Building trust-based ongoing relationships

Infrastructure initiatives that are seeking to establish relationships with Māori groups tend to face common challenges. These include identifying which Māori groups to engage with or who within a Māori group to engage with, challenges engaging with all the beneficial owners of multiple-owned Māori land affected by an infrastructure initiative, concerns about acquisition of land owned by Māori groups, and the need to budget or account for the costs of engaging with Māori groups.

To address these and other issues, our research shows a high degree of consensus between mana whenua groups and infrastructure sector participants in the need to establish and maintain enduring relationships between infrastructure providers and Māori groups.

Factors that both mana whenua groups and infrastructure providers see as necessary for such relationships to be established and maintained are that the relationships are based on trust with the parties:

- genuinely listening to what each other is saying

- having reasonably regular ongoing contact

- having a long-term focus and allowing the time for necessary conversations to occur

- genuinely seeking to address matters of importance to the Māori group (not only matters of importance to the infrastructure provider)

- taking a positive and constructive approach.

Source: ‘State of Play: Māori engagement in infrastructure. Huihuinga kaiwhakarato – hanganga Māori’. New Zealand Infrastructure Commission. (2024).

Economic regulation applies to commercial and local government infrastructure

Economic regulation can help with oversight and accountability. Often, this involves the Commerce Commission overseeing monopoly providers to replicate the effect of competition and ensure prices are fair, consumers are protected, and companies are customer-responsive and innovative.

Several types of economic regulation exist. These include information disclosure regulation where the Commerce Commission requires and publishes information on infrastructure providers’ performance. By contrast, price-quality regulation is where the Commerce Commission sets limits on how much revenue infrastructure providers can raise from users and the minimum service quality standards that must be met. Financial penalties can be imposed for not meeting compliance obligations, including service quality levels.

Economic regulation can work well for commercial infrastructure. Commercial providers must pay for investment using their own revenue streams. They also have the autonomy to make their own decisions about investment. For commercial providers, the Commerce Commission’s regulatory decisions can be binding on entities and financial penalties for poor performance provide a meaningful incentive to improve.

Economic regulation can also work well for local government. Unlike commercial entities, councils do not have a profit motive, but they are expected to pay for investment using their own revenue streams and can make their own decisions about investment. Where policy settings remain stable, the Commerce Commission’s oversight can be effective. The Commerce Commission will soon administer economic regulation of local government water and wastewater services, complementing the role of Taumata Arowai in regulating for safe drinking water. Stormwater could also be added in future by Order in Council.

Other tools can support the accountability of local government. For instance, performance benchmarking being developed by the Department of Internal Affairs has similarities to information disclosure.[46] Such a tool would allow ratepayers to compare the performance of their council to others. Accountability is similarly supported through existing audit provisions under the Local Government Act 2002. However, expectations for accountability can be challenged by frequent changes to central government policy settings, like freshwater policy, housing, water services and resource management, among others.

Central government oversees itself through the Investment Management System

Central government infrastructure requires different oversight mechanisms. Economic regulation is ineffective in this area. This is because it would require one Crown entity (the Commerce Commission) to oversee other public service entities (such as Health New Zealand or the Ministry of Education), when all are governed by Cabinet and Ministers and funded through the annual Budget. Consequently, regulatory decisions may not be binding if Cabinet chooses to override those decisions. Financial penalties for poor performance would not be meaningful either because the Crown would effectively be fining itself.

Transparency is needed to make central government accountable to the public. In the absence of economic regulation, it is especially important that essential information is available to the people who use and pay for public infrastructure and vote in elections. This includes information on infrastructure spending, asset management and investment planning, the condition of infrastructure assets and outcomes delivered through investment.

The Public Finance Act 1989 is the main transparency and accountability mechanism for central government.[47] The Public Finance System governs the use of public financial resources, including central government infrastructure assets and investment in those assets. The Government must report on its long-term fiscal objectives and short-term fiscal intentions.[48] The Act outlines principles of responsible fiscal management that the Government is expected to follow. These include requirements to maintain Crown debt at appropriate levels, as defined by the Government of the day, to ensure that operating expenses do not exceed operating revenues over a reasonable period, and to effectively manage fiscal risks.[49]

The Investment Management System provides oversight of central government agencies’ investment and asset management activities.[50] This is a component of the Public Finance System. It sets requirements for capital investment throughout the investment lifecycle, from problem identification to benefits realisation. Important requirements for central government agencies are set in a Cabinet Office Circular on investment management.[51]

The Treasury plays a significant role in overseeing central government infrastructure investment, alongside other agencies. The Treasury leads the annual Budget process and the implementation of the Investment Management System. The New Zealand Infrastructure Commission is designated as a system leader for infrastructure investment, advising on investment and asset management through the Investment Management System. National Infrastructure Funding and Financing Limited and Crown Infrastructure Delivery Limited provide specialist support on funding and financing and project delivery, respectively.[52]

Governance is clarified for land transport investment

Challenges facing land transport governance and oversight need to be addressed. Land transport is unusual, relative to other network infrastructure sectors like electricity and fixed-line telecommunications, because it does not have any external oversight or economic regulation.

Land transport is governed by sector legislation – the Land Transport Management Act 2003 – and provided by both local and central government. State highways and rail networks are provided by central government, and local roads and urban public transport services are provided by local governments. These networks must work together as a system to ensure investment is coordinated and the most cost-effective options for providing services are chosen.

Central government has established arms-length entities to provide networks. This includes a Crown agency, the New Zealand Transport Agency Waka Kotahi (NZTA), which provides state highways and co-funds local roads and urban public transport services, and a state-owned enterprise, KiwiRail, which provides rail infrastructure and services. Because NZTA co-funds local government spending, it helps to oversee their investment and performance, but it does not face external oversight of its spending plans and asset condition. In principle, these entities should be self-funding from user charges.

The Government Policy Statement on land transport directs spending in the sector. This allows the Minister of Transport to set objectives and priorities for land transport spending and define funding ranges for individual categories of investment. Recent Government Policy Statements, including for 2024, have also set expectations that NZTA prioritise specific investments, such as the Roads of National Significance. It is updated every three years, and the Ministry of Transport is responsible for monitoring outcomes against its objectives. In recent years, central government transport infrastructure providers have been expected to spend significantly more than they are able to collect in revenue, posing challenges for fiscal sustainability (Box 8).

Source: NZTA National Land Transport Programme 2024-2027.

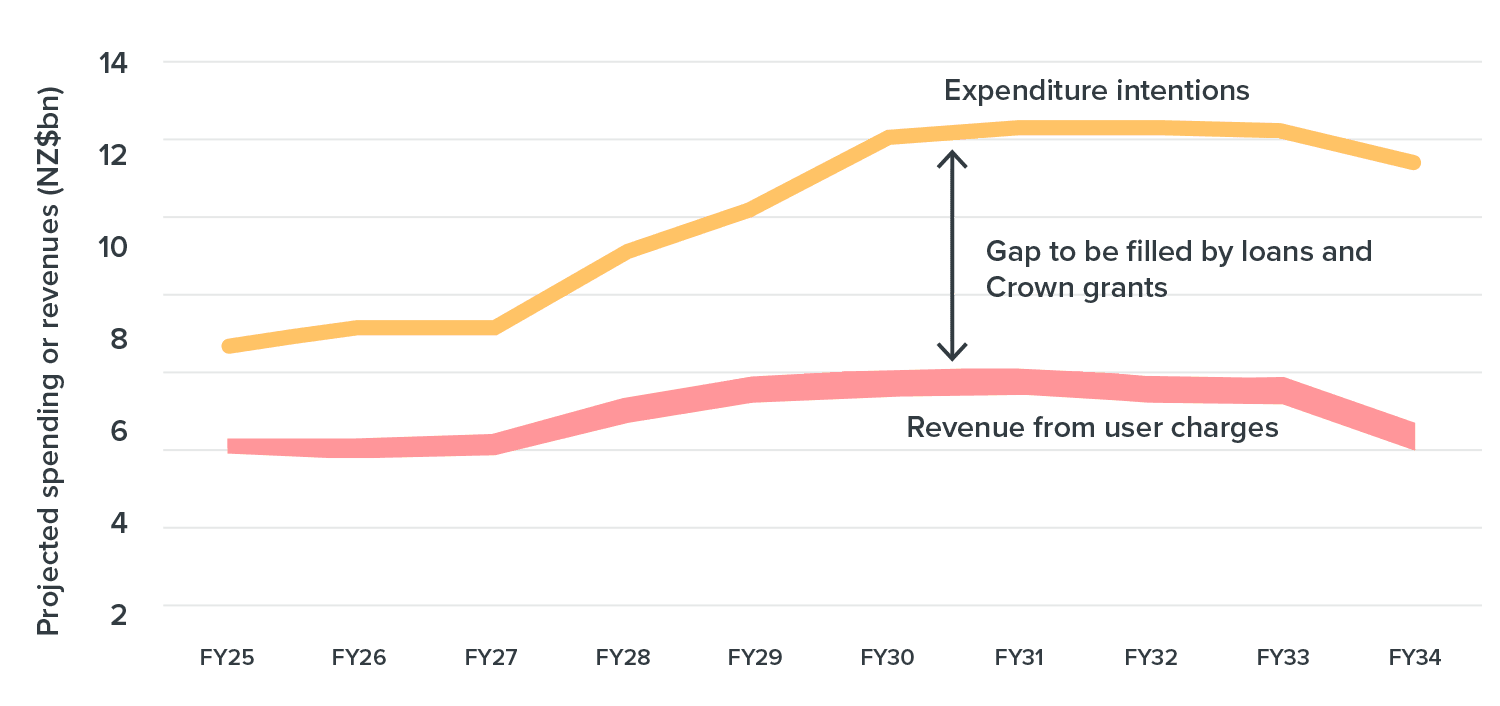

Figure 21: New Zealand plans to spend much more on land transport than it collects from users

Box 8

Land transport funding pressures

Land transport currently faces a misalignment between investment plans or expectations and the user revenue streams available to fund them. Since the late 2010s, central government spending on land transport (both road and rail) has significantly exceeded user revenues, and this is expected to continue over the next decade (Figure 21: New Zealand plans to spend much more on land transport than it collects from users).

The 2024–2027 National Land Transport Programme includes $32.9 billion in expenditure over a three-year period. Of this, $14.3 billion is available from transport user revenues and local government is expected to contribute $5.8 billion, leaving a gap of over $12 billion in a three-year period. This must be topped up by Crown grants and loans, in turn limiting the money that is available for other types of central government infrastructure. In early 2024, the Treasury identified a potential $27 billion to $38 billion gap between expenditure and revenue over the next 10 years.

4.2.3. Recommendations

Oversight and accountability mechanisms must be fit for purpose across all infrastructure sectors. We make two recommendations to address this. The first speaks to what is needed across all infrastructure sectors, while the second identifies a need for reform in a single sector – land transport – where investment intentions and user revenues are misaligned.

In Section 5, we make further recommendations on steps that are needed to strengthen the Investment Management System.

These recommendations are important for ensuring that infrastructure providers have a clear authorising environment for investment and invest in response to New Zealanders’ needs.

Recommendation 4

Consumer protection: All infrastructure providers, regardless of sector have clear and well-understood transparency and accountability mechanisms that ensure that consumer interests are protected.

This recommendation would need to be implemented through policy and operational changes, which we are investigating further.

Recommendation 5

Transport system reform: The land transport funding gap is closed by requiring user charges to fully fund planned investment.

This recommendation would need to be implemented through policy and operational changes, which we are investigating further. To address identified issues, we expect implementation to address decision-making about investment priorities and land transport pricing.