Content

Content

Draft National Infrastructure Plan

3.4. Infrastructure workforce must grow | Me tipu te rāngai mahi tūāhanga

3.4.1 Context

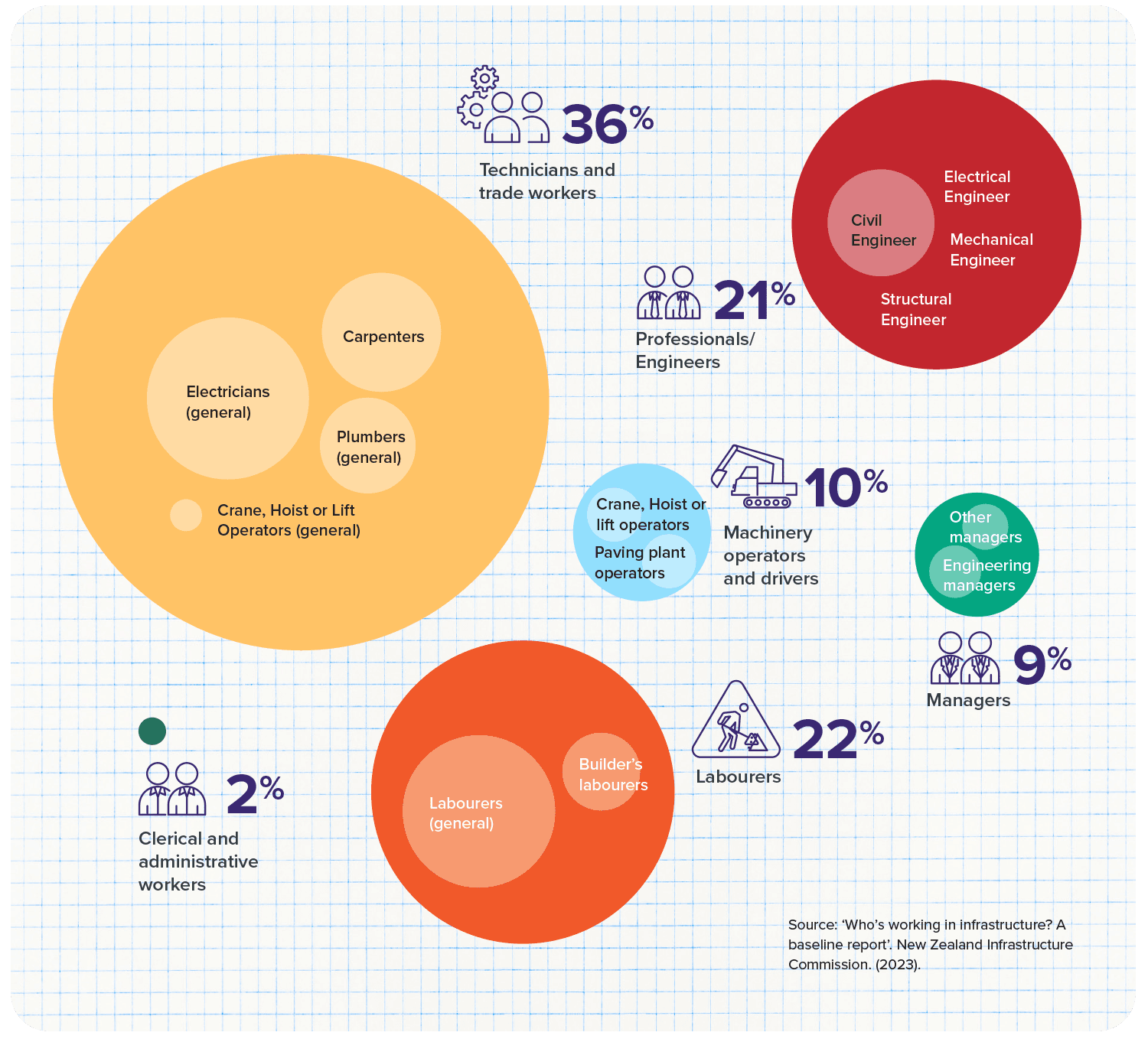

New Zealand needs a workforce that is productive, efficient, and sized right for the job. The existing infrastructure workforce comprises more than 100,000 full-time equivalent workers spread across more than 100 distinct occupations. Different skills are needed in planning, design, construction and maintenance of infrastructure (Figure 17). Importantly, constructing new projects accounts for less than half of the workforce. Around 14% of infrastructure workers are engaged in planning and design, 46% are constructing new assets, and a further 40% of infrastructure workers are engaged in asset management and maintenance.

Different occupations are engaged at various stages of the infrastructure lifecycle

Source: ‘Who’s working in infrastructure? A baseline report’. New Zealand Infrastructure Commission. (2023).

Figure 17: Breakdown of the workforce by infrastructure lifecycle stage, 2022–2024

3.4.2 Strategic direction

Long-term forward guidance is used to plan for a larger workforce

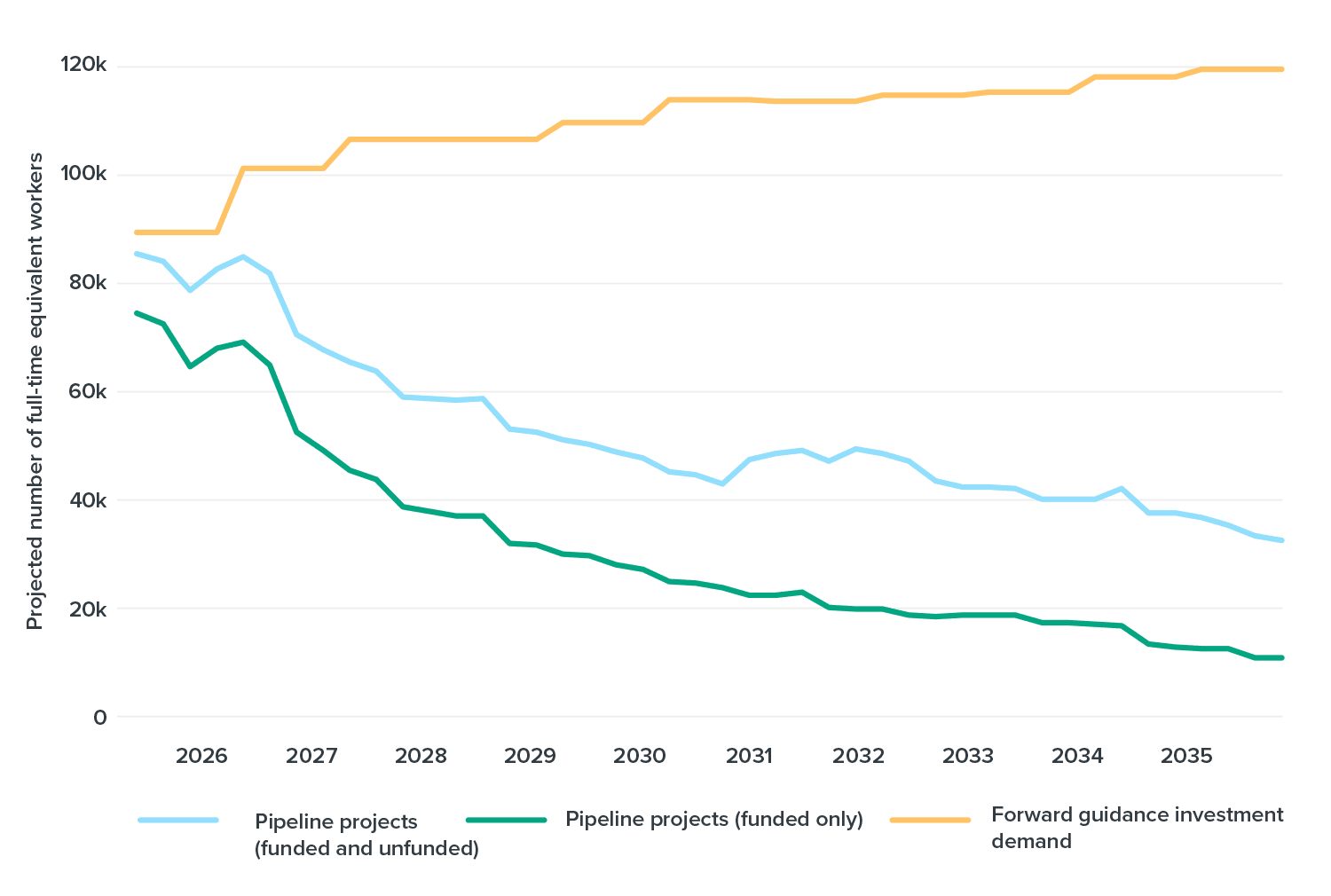

More infrastructure investment will require more workers. We convert our forward guidance into estimates of future workforce demand for renewal and replacement of existing infrastructure and construction of new and improved infrastructure. These suggest that the total size of the infrastructure workforce will gradually increase over the next 30 years (Figure 18). Because New Zealand’s population will grow older, a larger share of the working-age population will be engaged in the infrastructure workforce. However, a limitation for this modelling is that workforce needs will be affected by future productivity trends, which are hard to forecast but can add up over a multi-decade period.

Our forward guidance paints a different picture of workforce demand than project intentions. The National Infrastructure Pipeline, covered in Section 6, compiles information on most infrastructure providers’ current projects and their future project intentions. We model the workforce that would be required to deliver on these intentions. Because infrastructure providers do not plan projects in detail a long way in advance, project-specific workforce demands tail off after a few years.

Our forward guidance provides a longer-term view that can be useful for workforce policy. If longer-term infrastructure investment demand forecasts are used to inform other planning and funding processes, they will also provide a credible forward view that can be used to inform workforce development activities, such as vocational training and immigration policy settings. They can help us to get past short-term uncertainties about which projects will proceed.

Getting there requires consistent investment decisions. New Zealand’s infrastructure workforce is mobile domestically and internationally. It is hard to recruit, develop, and retain skilled people when there is significant uncertainty about the volume of civil, commercial, and residential construction work.

A longer-term outlook for infrastructure investment can get workforce planning beyond the near term

Source: Infrastructure Commission analysis of workforce requirements to deliver our forward guidance on investment, compared with workforce requirements to deliver specific projects currently reported to the National Infrastructure Pipeline.

Figure 18: Future workforce demand to deliver forward investment guidance, compared with workforce demand for infrastructure providers’ near term project intentions

Infrastructure providers build and maintain capability to deliver

Government needs to be a sophisticated client of infrastructure. Central and local government infrastructure providers must build and maintain their people capability to lead and deliver complex projects successfully.

Government infrastructure providers can procure required design and construction services from engineering and construction firms. However, to be effective clients, they must have the internal capability to shape scope, oversee delivery, manage performance and remain accountable for outcomes. This is essential for central and local government infrastructure providers to manage risk and achieve value for money and cannot not be contracted out.

Improving procurement means developing project leadership and governance capability. Capability exists within agencies and in Crown Infrastructure Development Ltd, which was established to lead the safe, efficient, and cost-effective delivery of quality infrastructure projects for Crown organisations. But more is needed to ensure that important capabilities required for successful project planning and delivery are available throughout the sector.

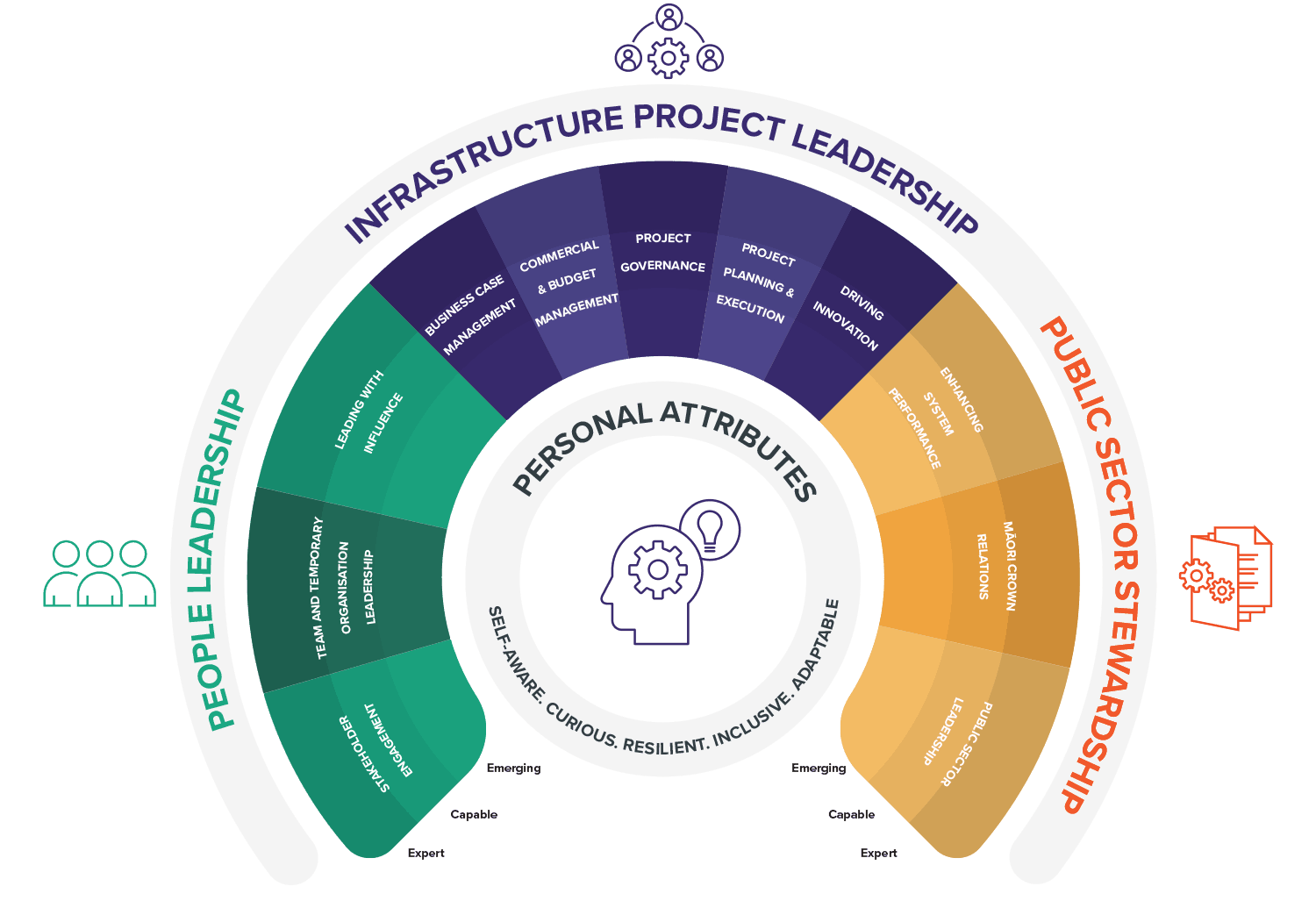

People capability is essential. We need to develop and invest in the individuals holding important project roles, including project directors and senior responsible owners (who are typically called “project sponsors” in commercial infrastructure providers) (Figure 19). This requires a sector-wide approach to establish pathways for formal development, stretch assignments, secondments, or progression between projects.

Improved governance can improve project delivery. Public sector infrastructure leaders are often required to operate within unclear, fragmented, and overlapping governance structures, which reduce clarity and slow decision-making. This observation is reflected across multiple system reviews. The Treasury Gateway Lessons Learned data identifies governance confusion as a recurring issue contributing to project delays.[39] Similarly, the OECD’s Infrastructure Governance Indicators report rates New Zealand as below the OECD average in six of eight governance indicators.[40]

The Commission has begun addressing these gaps through a suite of leadership initiatives. The Project Director Capability Framework provides a nationally consistent benchmark for the capabilities required to lead complex infrastructure projects and has already been used to inform recruitment, development, and self-assessment tools across agencies. Complementing this, the Commission has developed best practice guides and recruitment tools to support better decision-making around the appointment of senior responsible owners and the recruitment of project directors. This ensures the right people are placed in the right roles with greater clarity and consistency.

Developing a nationally consistent benchmark for project director capability

Source: ‘Public Sector Project Director Capability Framework’. New Zealand Infrastructure Commission. (2025).

Figure 19: Public sector Project Director Capability Framework

The sector establishes broader pathways into the workforce

The infrastructure workforce needs to draw on a wider talent pool to grow and meet demands. In the near term, our ability to deliver more infrastructure is limited by the current size, composition and regional location of the workforce.

The infrastructure workforce is younger than the overall New Zealand workforce. The occupations with the highest share of people aged 55 and over are electrical engineering technician (30% aged 55 and over), telecommunications technician (30%), engineering manager (28%), builder's labourer (27%) and programme or project administrator (27%). These occupations will face slightly higher medium-term needs to train and recruit younger workers as older cohorts retire. Opportunities exist to lift engagement and ensure that training and recruitment pipelines are accessible. This will be important if we are to continue to meet our workforce needs.

Māori make up a growing share of the infrastructure workforce. At a national level, Māori workers make up 18% of the overall infrastructure workforce. Māori are more strongly represented in younger cohorts across most occupations. At present, labouring and machinery operating and driving occupations tend to have a higher-than-average share of Māori workers (27% and 30%, respectively). In New Zealand’s overall workforce, 46% of Māori workers are now in high-skilled jobs, compared with 2018 when 37% of Māori were in high-skilled jobs. Additionally, between 2013–2023, Māori-owned construction businesses increased by over 35%.[41] These shifts reflect an opportunity for change within the infrastructure sector when it comes to recruiting Māori workers across a wider range of infrastructure occupations.

Women only account for 11% of the infrastructure workforce, compared with 47% of the overall New Zealand workforce. Women make up a small minority of workers in all main categories of infrastructure occupations except clerical and administrative occupations. About one-fifth of professionals, such as engineers, are women, and 15% of labourers are women. Moreover, younger age cohorts have a similar share of women as older age cohorts, suggesting that gender balance won’t change as older workers retire. These patterns may reflect ongoing challenges with both recruitment and retention of women in the infrastructure workforce.

3.4.3. Recommendations

Changes are needed to ensure that we develop an infrastructure workforce that has the right capacity and capability to deliver on future investment demands.

We make two main recommendations to improve workforce development planning and policy and to lift government’s project leadership capability.

These recommendations are important for ensuring that we take steps to recruit, develop, and retain the skilled workforce required for infrastructure.

Recommendation 1

Workforce development: Workforce development planning and policy is informed by infrastructure investment and asset management plans and the New Zealand Infrastructure Commission’s independent view of long-term needs.

This recommendation would need to be implemented through policy and operational changes, which we are investigating further.

Recommendation 2

Public sector capability: Public sector project leadership is strengthened by standardising role expectations and improving career pathways.

This recommendation could be implemented by:

- Creating a clear, nationally recognised benchmark for leadership and delivery expertise, giving agencies and investors’ confidence that leaders who meet this benchmark can manage risk, navigate complexity, and deliver value.

- Establishing a sector-wide secondment and career development model to attract experienced practitioners from other sectors, support progression, cross-agency mobility, and the retention of high-performing infrastructure leaders.

- Requiring agencies to adopt nationally consistent role definitions, appointment criteria, and performance expectations for senior responsible owners and project directors, using tools such as the Project Director Capability Framework and best practice appointment guides.