Content

Content

Draft National Infrastructure Plan

5.3. Lift the bar for project appraisal, selection and delivery | He hiki i te kounga o te arohaehae, te kōwhiri me te whakatutuki i ngā kaupapa

5.3.1. Context

Long-term planning is not a comprehensive answer to ensuring good infrastructure outcomes. Even when investment intentions are better aligned to service needs, funding for investment will remain constrained. Investing in one area will come at the cost of other services. Consequently, a need exists to lift the bar on project quality and consider a project mix that speaks to infrastructure needs from across the country.

Decision-makers need confidence that capital investments are strategically aligned with long-term outcomes, provide good value for money and are deliverable. This means assessing whether we are solving genuine problems, whether the cost of the project is proportionate to the size of the problem and whether the proposed solution will deliver the benefits it promises. Further, confidence is needed that agencies have the right capability to successfully deliver on planned investment. This includes investing in post-implementation reviews, to ensure we capture realised benefits and lessons from past projects.

Project planning requirements are sound, but implementation needs to improve. The Investment Management System includes guidance for project business case development and provides processes for reviewing investment. However, further work is needed to provide confidence to decision-makers and the public that projects are ready to be funded and delivered.

5.3.2. Strategic directions

Central government agencies adhere to best practice project planning guidelines

Agencies need to ‘think slow and act fast’ when planning new infrastructure projects. They can do this by developing business cases that clearly define a problem or opportunity, test options for addressing it, select a solution that delivers the best value for money, and progress project planning such that it can be funded for delivery. For large or complex projects, a multi-stage planning approach is needed to ensure that the project is adequately developed before a funding decision.

Cabinet approval is required for all significant new capital expenditure. Central government agencies typically need to submit Budget bids for new capital expenditure or seek Cabinet approval of business cases to undertake new projects or investment programmes. Under the Investment Management System, agencies are expected to follow best practices for developing investment proposals before moving to delivery. This includes following the Treasury’s Better Business Cases guidance, which outlines a best-practice stage gate process for project planning.

The Treasury monitors compliance with these requirements. It convenes an Investment Panel that provides advice to Ministers on large investment proposals before their Budget decisions.[81] All infrastructure proposals seeking Budget funding are required to complete and submit a Risk Profile Assessment to the Treasury for review. The Treasury then determines the level of central scrutiny that will apply to the project. Projects with medium- and high-risk ratings will be required to provide information to the Treasury’s Quarterly Investment Reporting, which is proactively released.

High-risk projects are also required to undergo Gateway assurance reviews. Gateway reviews the risks of the project at its various stage gates, but does not assess the broader quality of the project. Findings from Gateway reviews are provided to agencies but not proactively released. As a result, it is unclear whether all relevant projects are receiving Gateway reviews and whether risks identified in them are well managed. At Budget 2022, the Treasury’s Investment Panel noted that ‘risks in the delivery of the preferred solution were insufficiently assessed’ for most proposals.[82]

Compliance with project planning requirements increases

All investment proposals should complete robust business cases before seeking Budget funding. The need exists to get beyond reactive planning and premature announcement of new projects. But this will be difficult if projects can obtain funding without high-quality project planning.

Good information can build confidence in projects. Projects with robust business cases are less vulnerable to cost overruns and delivery delays. These projects are also less likely to be rescoped, defunded or delayed by future decision-makers. This is because they are more likely to be addressing specific problems or opportunities through solutions that provide good value for money.

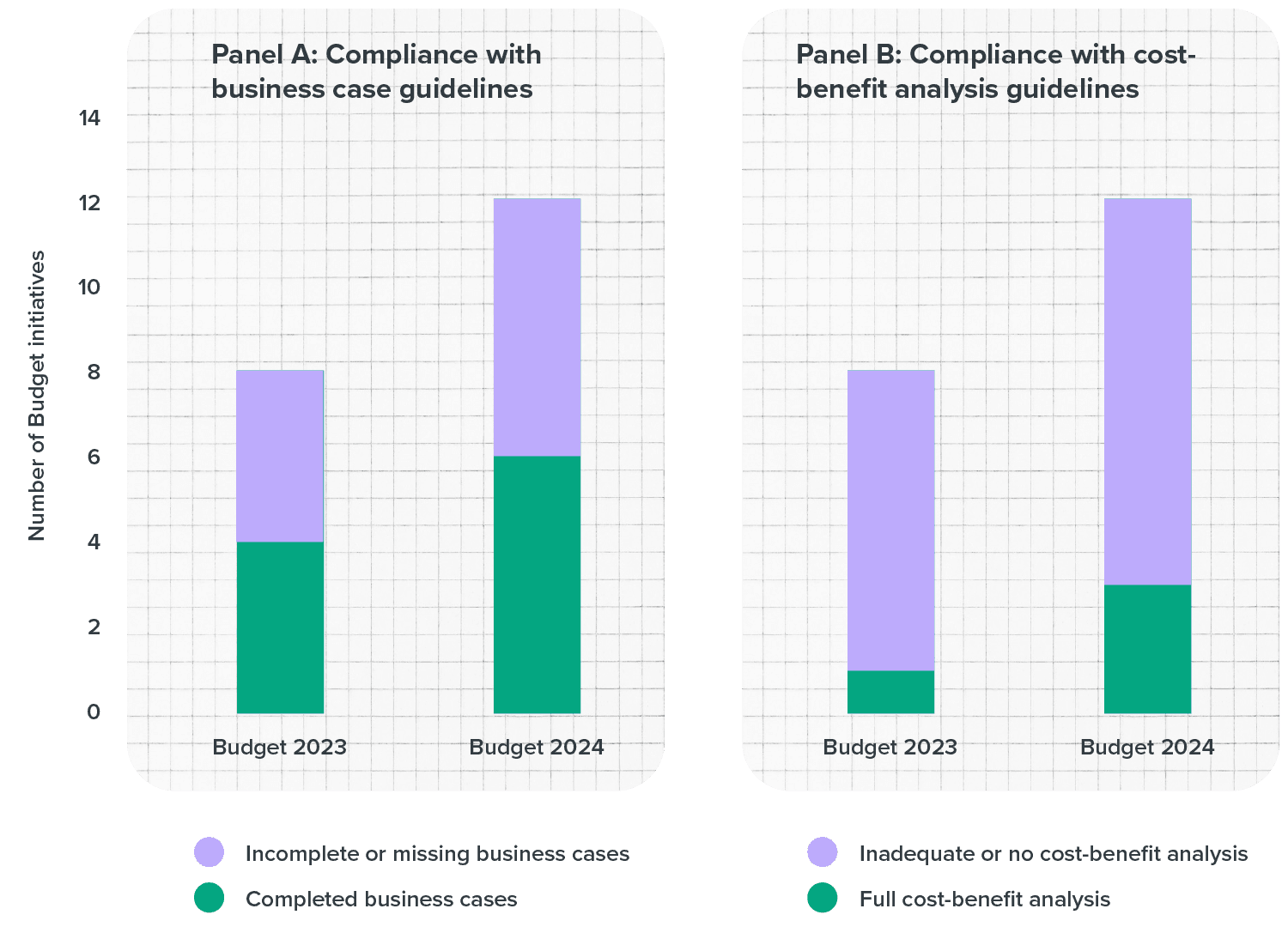

Many investment proposals are submitted for Budget funding without robust business cases. Despite existing requirements for well-developed business cases, half of the Budget bids reviewed by the Treasury’s Investment Panel for the 2023 and 2024 Budgets had missing or incomplete business cases (Figure 30). This continues a trend from the 2021 and 2022 Budgets. Moreover, almost all Budget bids lacked cost-benefit analysis information, making it hard to understand whether they have identified the most cost-effective solution.

Half of all Budget bids had missing or incomplete business cases

Source: ‘Annual report’. New Zealand Infrastructure Commission. (2024).

Figure 30: Compliance with business case and cost-benefit analysis guidance among Budget infrastructure project funding bids reviewed by the Treasury’s Investment Panel in 2023 and 2024

Project quality and readiness is rigorously tested before a funding decision

Project planning should guard strategic alignment, value for money and deliverability for new investments. To be worth funding, projects should demonstrate that they are addressing an important problem or opportunity, that they have identified the most cost-effective solution, and they are set up to successfully deliver (Box 14). Decision-makers’ objectives will change over time (equivalent to a change in strategic priority). However, the fundamentals of value for money and deliverability do not change. A project that has not completed adequate project scoping or site investigations will not become easier to build if assessed against different strategic priorities.

Business cases should not force decision-makers to choose between an expensive project and an unsolved problem. They should consider a range of options, including low-cost and non-built solutions that avoid the need for new infrastructure, rather than focusing on a narrow set of costly solutions. In some cases, a high-cost option that delivers high benefits over the life of the new asset may still be the most cost-effective way to solve a problem. But often, lower-cost solutions will deliver higher value for money, or better balance fiscal affordability constraints.

A consistent and high bar is needed for investment. It is difficult to track whether value for money and deliverability are improving over time because the Treasury’s Budget Evaluation Framework, which it uses to assess Budget bids for new capital investments, changes significantly every year.[83] Core elements of evaluation frameworks should be stable over time. They should also set a high bar for value for money, seeking projects that maximise the benefits achieved from investment under various possible scenarios, rather than propositions where benefits exceed costs only under optimistic assumptions.

Box 14

What makes a good infrastructure project

Our work in the Infrastructure Priorities Programme considers infrastructure proposals against three main criteria:

- Strategic alignment: Does a proposal support future infrastructure priorities and/or improve existing infrastructure systems and networks that New Zealanders need?

- Value for money: Does a proposal provide value to New Zealand above the costs required to deliver, operate, maintain and dispose of it?

- Deliverability: Can a proposal be successfully implemented and operated over its life?

Large, nationally important infrastructure projects are expected to go through several stages of planning before a funding decision. This starts with a Strategic Assessment (stage 1) that defines the problem or opportunity that the project can address, continues to an Indicative Business Case (stage 2) that identifies and tests different options, and then to a Detailed Business Case (stage 3) that identifies a preferred option and ensures that it is deliverable. The focus of assessment changes across these three stages.

Source: ‘Infrastructure Priorities Assessment Framework’. New Zealand Infrastructure Commission. (2024).

Agencies act as sophisticated clients of infrastructure

Project planning is only the first step in delivering good infrastructure. Central government agencies also need to set themselves up for success in the delivery phase. This means investing in internal capability to become a more sophisticated client of infrastructure and looking for opportunities to engage with supply chains through win-win commercial relationships that support productivity.[84]

Agencies must start by lifting their own internal capability to engage the market. A whole-of-system approach is required when planning projects and engaging the market. Agencies must identify how they will use procurement relationships to deliver outcomes and establish a robust framework for determining the value of what they are buying.

Agencies also need to change how they engage their supply chains. While traditional, transactional procurement models work for many projects, integrated, collaborative procurement models can provide additional benefits when managed well. To make this work, agencies must create aligned commercial relationships, which ensure cost-effective delivery of public investment and good commercial opportunities for private sector partners. They must develop integrated teams to deliver projects, use digital tools and data to drive efficiencies, and adopt a ‘production system’ approach to standardise repeatable projects.

Transparent information on past projects is used to improve future practice

Continuous improvement is needed to lift productivity and improve future project planning. Information on past projects can help future projects learn how to replicate successes and avoid risks. To do this, important project information from the planning and delivery phase must be preserved in an accessible and transparent form, and reviewed to identify system-wide lessons.

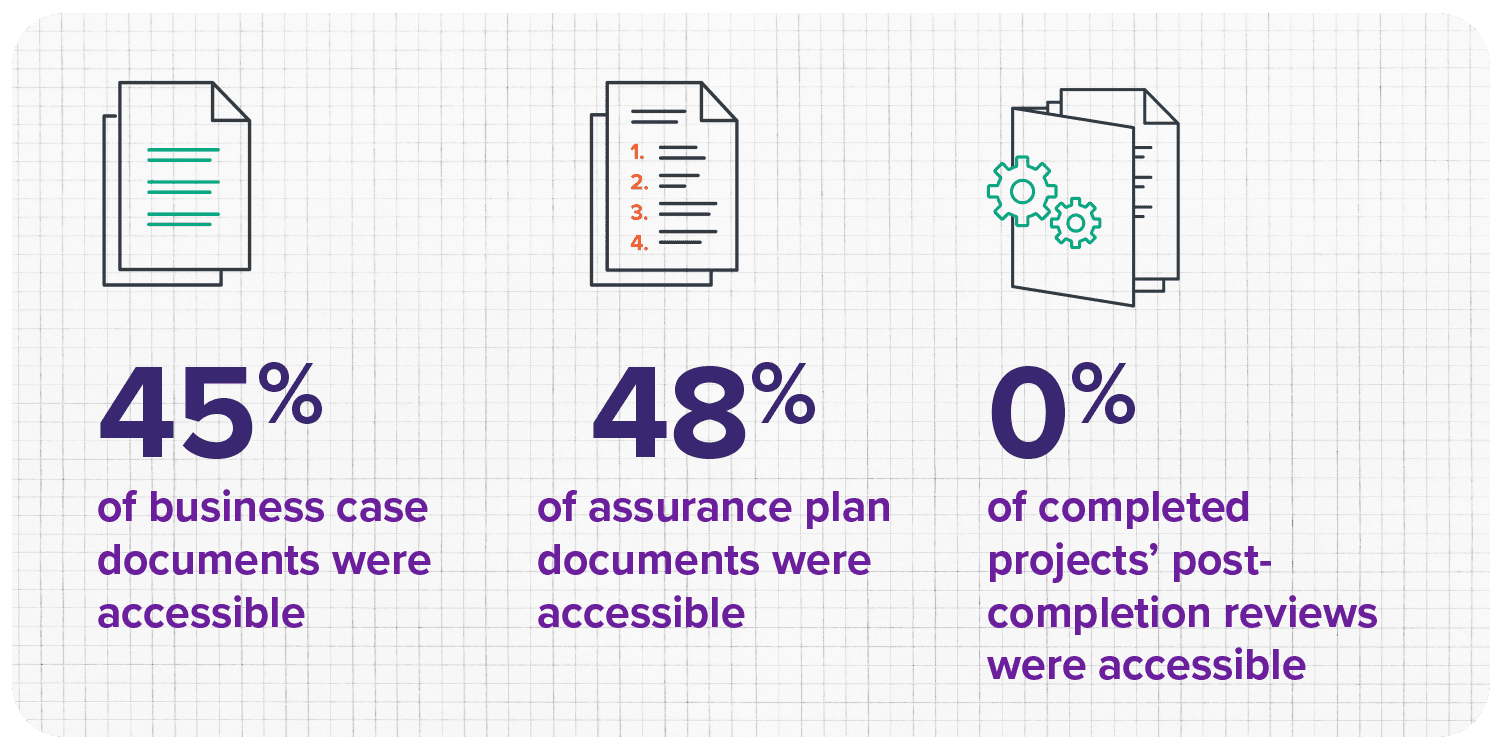

Project transparency and retention of significant data are needed to enable learning. Important project documents, such as business cases and assurance plans, are unavailable for many large publicly funded infrastructure projects (Box 15). Furthermore, data on project costs, completion dates, and benefit realisation should be systematically captured after projects are delivered.[85]

Structured post-completion reviews can help identify system-wide issues affecting projects. The Commission is undertaking work to establish a post-completion review programme to deliver on Recommendation 17 of the Infrastructure Strategy. This will look at completed major infrastructure projects to systematically compare what actually happened against what was expected in the planning phase. Findings can inform future project evaluation methods, investment decision-making, and system-wide improvements.

Source: ‘Transparency within large publicly funded New Zealand infrastructure projects’. Massey University. Prepared for the New Zealand Infrastructure Commission. (2023).

Box 15

Transparency of important project documents for large publicly funded infrastructure projects

Massey University researchers reviewed the accessibility of documents for 27 large projects across central and local government. These range in cost from $50 million to more than $1 billion and have a collective value of over $70 billion.

Key project documents were inaccessible for over half of the projects that were reviewed. All projects with the best document accessibility were run by an independent board, rather than a government agency or council, and nearly all were in the $500 million plus project category.

Source: ‘Transparency within large publicly funded New Zealand infrastructure projects’. Massey University. Prepared for the New Zealand Infrastructure Commission. (2023).

5.3.3. Recommendations

Changes are needed to lift the bar for project appraisal, selection, and delivery in central government. We make four main recommendations to improve policy and practices in this area. They are intended to ensure that adequate independent review is undertaken of investment proposals in the planning stages, that risks are well managed through project assurance, that important project information is transparently available, and that we have the information needed for continual improvement.

These recommendations bolster our advice on long-term asset management and investment planning. For long-term planning to be successful, we need to ensure projects are progressed in a methodical and consistent way, and risks are well managed through the investment lifecycle. This is important for ensuring that decision-makers and the public can have confidence in new investments.

Recommendation 14

Investment readiness assessment: All Crown-funded infrastructure proposals pass through a transparent, independent readiness assessment before funding.

This recommendation could be implemented by:

- Mandating participation in the Infrastructure Priorities Programme for central government infrastructure proposals and non-central government projects that are seeking Crown funding.

Recommendation 15

Project transparency: All business cases, Budget submissions, and advice on central government infrastructure investments are published.

This recommendation could be implemented by:

- Requiring, as the default position, the publication of all business cases, budget submissions and advice relating to infrastructure investment proposals to improve transparency.

Recommendation 16

Risk management: Project assurance for central government agencies ensures that risks are well managed.

This recommendation could be implemented by:

- Considering opportunities to improve the end-to-end assurance process for infrastructure projects, including the independent quality assurance of business cases to provide Ministers with greater confidence of project success and visibility of significant projects’ risks.

Recommendation 17

Learning from projects: Post-completion information on actual project costs, delivery dates and benefits are provided and published in a standard format, enabling comparisons to what was expected when funded.

This recommendation could be implemented by:

- Requiring central government agencies, local governments, and potentially other infrastructure providers to regularly submit project information to the National Infrastructure Pipeline.

- Requiring provision of additional project data for major projects, including business case cost estimates, actual delivery costs, delivery target date, actual delivery date, business case forecasts of benefits, and actual realised benefits.